Near Humpback Rocks, in rural Virginia, an exhibit known as the William J. Carter farmstead is open to visitors who are curious about what mountain life was like in the late 1800s. The land was purchased by Carter in the late 1800s for $3 an acre, paid for in Confederate money. In the 1950s parkway planners moved period buildings from other areas and arranged them on the property to show what a typical 19th century mountain farm might have looked like.

The self-guided trail at the Carter farm meanders past a cabin, weasel-roof chicken coop, root cellar, a barn with a bear-proof hog pen, spring house, a lye hopper, and a household vegetable garden enclosed within a rustic wooden fence.

The self-guided trail at the Carter farm meanders past a cabin, weasel-roof chicken coop, root cellar, a barn with a bear-proof hog pen, spring house, a lye hopper, and a household vegetable garden enclosed within a rustic wooden fence.

Log cabins such as this were very common in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Trees were felled on the property and would be squared off with a broad axe and foot adz, which left their mark in the rough-hewn walls of the cabin. After the logs were cut and hewn, they would be dove-tailed together at the notches in the end to form the walls. Roofs were typically covered with cedar or oak shakes that were hand split on the site. The spaces between the logs were chinked with pieces of wood cut to fit and daubed with mud mixed with horse hair for strength and “stickability.” The fireplace served to cook meals and heat the home in winter.

As the family grew, they would often add an addition next to the original cabin and connect the two with a breezeway called “dog-trot.” Many times, a separate building that housed a kitchen was not connected to the cabin so that in case of fire the main home would be spared.

Every homestead was situated near a spring so fresh cold water was available at any time. A springhouse was usually built over top of the spring and served as a refrigerator that kept milk, butter and eggs cool and fresh.

Every homestead was situated near a spring so fresh cold water was available at any time. A springhouse was usually built over top of the spring and served as a refrigerator that kept milk, butter and eggs cool and fresh.

An ash hopper was used to make lye, which was mixed with fat from the fall butchering to make soap that the family used to wash themselves as well as their clothes. Ashes from the fireplace were dumped into the hopper and water was poured over them. The resulting product was lye, which was collected from the bottom drain and used when needed.

An ash hopper was used to make lye, which was mixed with fat from the fall butchering to make soap that the family used to wash themselves as well as their clothes. Ashes from the fireplace were dumped into the hopper and water was poured over them. The resulting product was lye, which was collected from the bottom drain and used when needed.

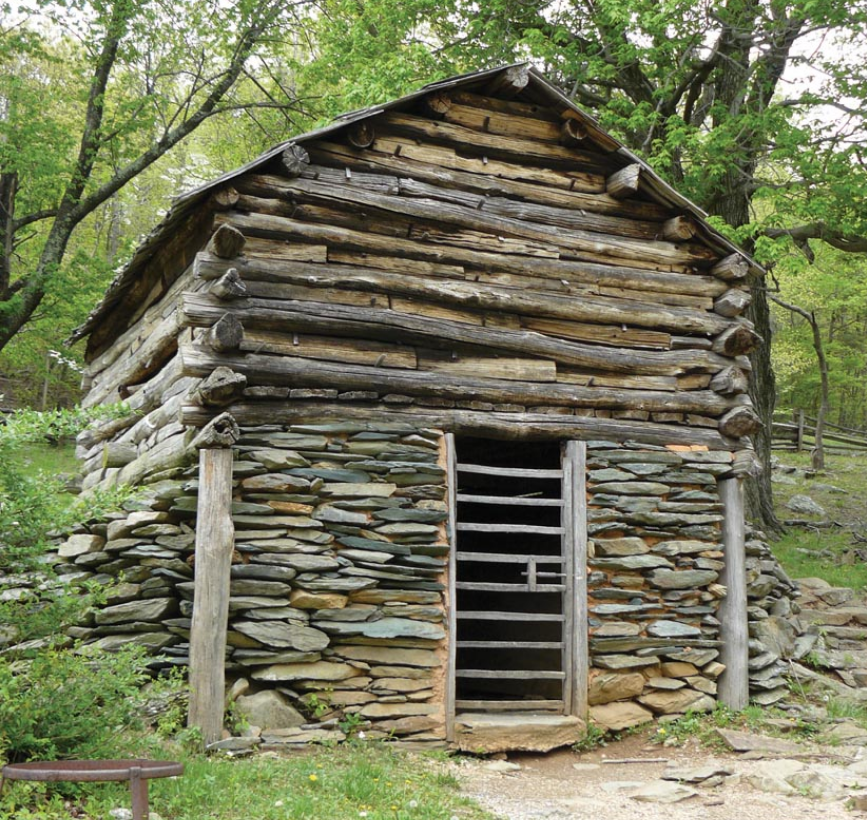

The barn was an essential part of a homestead, housing equipment and feed, and providing shelter for the livestock. Rails split from durable and long-lasting chestnut wood were used for fencing along with the abundance of rocks found throughout the mountains. These fences marked boundaries and kept farm animals in while keeping predators out.

The barn was an essential part of a homestead, housing equipment and feed, and providing shelter for the livestock. Rails split from durable and long-lasting chestnut wood were used for fencing along with the abundance of rocks found throughout the mountains. These fences marked boundaries and kept farm animals in while keeping predators out.

Fruit trees, such as apples, pears, plums, and peaches, provided a welcome addition to the family diet. Varieties of each species were used in different ways. Some apples dried well, others were extremely juicy for making drinks, while some were long-keeping and stored well over long periods of time.

Every homestead had a root cellar, dug into a hillside where fresh and canned vegetables and fruits could be stored on shelves and in wooden bins until needed. Cured meat such as smoked hams and bacon were hung from the rafters.

A flock of chickens kept the family in eggs and meat, but it was a test of endurance to keep them safe from predators. All cracks in the henhouse were chinked with small pieces of wood and a stout door with wooden pegs was a deterrent to most varmints looking for an easy meal.

Gardens provided fresh vegetables to the family and the crops were protected from unwanted pests and wildlife by enclosing its perimeters with wooden fencing. Scarecrows were erected in or around the garden in the hopes of deterring deer and bear from eating the plants. Lime was used to keep worms and other insects at bay. A typical mountain crop in 1890 might have included corn, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, okra, squash and pumpkins. An herb garden was handy for flavoring meals that otherwise might have tasted bland.

Gardens provided fresh vegetables to the family and the crops were protected from unwanted pests and wildlife by enclosing its perimeters with wooden fencing. Scarecrows were erected in or around the garden in the hopes of deterring deer and bear from eating the plants. Lime was used to keep worms and other insects at bay. A typical mountain crop in 1890 might have included corn, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, okra, squash and pumpkins. An herb garden was handy for flavoring meals that otherwise might have tasted bland.

Today, people may walk the self-guided trail through the William Carter farmstead, which was originally a land grant tract given by the Commonwealth of Virginia to induce pioneers to settle the Blue Ridge Mountains and establish the border of the western frontier. Looking at the primitive way of life these hearty people lived without any modern conveniences, one has to respect the hardships they endured just to have a piece of land to call their own.

You can read the original article at www.crozetgazette.com