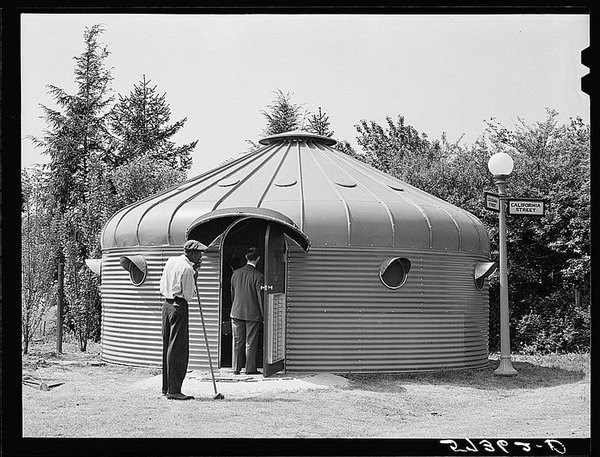

“Camp Evans, a decommissioned Army base in Wall Township, N.J., is frozen in midcentury, its brick administration buildings and boarded-up Quonset huts on hold from World War II. Fred Carl, 59, a former high school science teacher and the unofficial keeper of the site, leads a visitor to other throwbacks from that era: a collection of corrugated metal houses with porthole windows and conical roofs. They look like alien habitations dropped from the sky.

These are the only known surviving examples of the Dymaxion Deployment Units that R. Buckminster Fuller designed as an answer to wartime housing needs. Conceived as low-cost, mass-produced shelters that could comfortably accommodate a family of four, the units, known as D.D.U.s, were manufactured in the early 1940s and distributed to military bases around the world. But the war that inspired them would eventually put them out of production.

For a long time, it seemed that the D.D.U.s had disappeared from the earth, but they are not quite extinct, and Mr. Carl, along with local politicians, preservationists and sympathetic citizens, can be thanked for that. If the Army had had its way with Camp Evans, he said, “this would all have been demolished.”

The idea for the D.D.U.s came to Fuller in November 1940 while he was driving through the Midwest with a friend, the novelist Christopher Morley. The men were on a quixotic hunt for lost letters written by Edgar Allan Poe. En route, Fuller became fascinated with metal grain bins lining the Illinois roadsides. He discovered that they were made by the Butler Manufacturing Company of Kansas City, Mo.

Europe was at war, and the newspapers were filled with stories about Blitz-ravaged London. Fuller began to envision how the utilitarian structures might be converted into emergency housing. His idea was to transform Butler’s galvanized steel containers (“Safe from fire, rats, weather and waste,” their slogan promised) so they could be shipped anywhere in the world and assembled quickly as bombproof shelters.

Their usefulness would not end there. In peacetime, Fuller proposed, they could be sold as low-cost vacation bungalows for civilians. Butler’s early advertising campaign showed a D.D.U. planted in the woods with collapsible lounge chairs near the door; inside, a family gathered around a kidney-shaped coffee table.

By April 1941, the first D.D.U. prototype was off the Butler assembly line, and Fuller was presenting it to the Division of Defense Housing Coordination in Washington. Erected along the Potomac River, the structure was 12 feet high and 20 feet in diameter, with 10 porthole windows and 15 small skylights. Walter Sanders, an architect, agreed to “test dwell” the unit for several days with his wife.

As advertised, the unit cost $1,250 and came complete with lightweight furnishings and appliances from Montgomery Ward, including a kerosene-powered icebox and stove. Inside, the industrial rawness was softened with drapes over the portholes and a fireproof curtain weighted with tire chains designed to divide the interior into four pie-shaped rooms. Air circulated through an adjustable ventilator in the roof, and the floors were made from Masonite one-eighth of an inch thick.”

Source: New York Times

A modern version called Safe T Homes is still produced by the grain bin company Sukup in Sheffield, IA. View at sukup.com under their buildings tab.

Yes, we did a blog post about Sukup grain bin homes a while back that was quite popular. Also, a fair number of people are repurposing old grain bins and turning them into homes.

Where do I send my check for $ 1,250 ?

Looks like it could be turned into a UFO.

Search our site for modern homes built with grain bins.