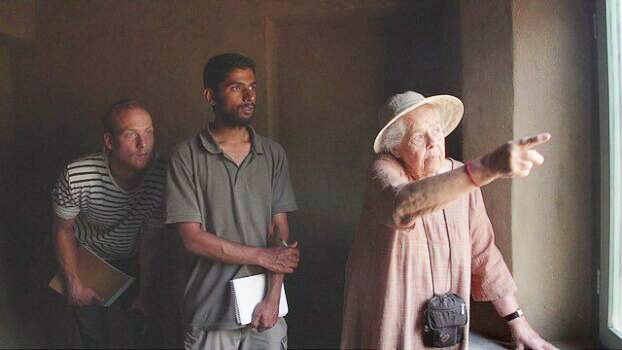

Didi Contractor, a self-taught architect from Dharamsala, India, left an indelible mark with her innovative approach to building with natural materials.

Didi Contractor (1929 – 2021) whose real name was Delia Kinzinger, was born in the USA. Her father was a German and her mother was an American, who were both renowned painters belonging to the Bauhaus group in the early 1920s. Delia grew up in Texas and spent some time in Europe also.

Didi Contractor (1929 – 2021) whose real name was Delia Kinzinger, was born in the USA. Her father was a German and her mother was an American, who were both renowned painters belonging to the Bauhaus group in the early 1920s. Delia grew up in Texas and spent some time in Europe also.

At the age of 11, she heard Frank Lloyd Wright and saw an exhibition of his works along with her parents. This made a lasting impression on her mind and developed her inclination for the profession of architecture. But her parents never encouraged her to pursue architecture and she completed her graduation in art at the University of Colorado.

At the age of 11, she heard Frank Lloyd Wright and saw an exhibition of his works along with her parents. This made a lasting impression on her mind and developed her inclination for the profession of architecture. But her parents never encouraged her to pursue architecture and she completed her graduation in art at the University of Colorado.

During her university days, she fell in love with Ramji Narayan, an Indian civil engineering student. They got married, returned to India, and raised a family with three children. Eventually she had to part ways with her husband and decided to settle in a small village near Dharamshala.

During her university days, she fell in love with Ramji Narayan, an Indian civil engineering student. They got married, returned to India, and raised a family with three children. Eventually she had to part ways with her husband and decided to settle in a small village near Dharamshala.

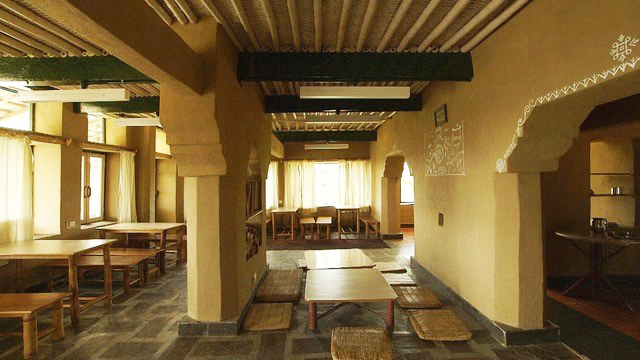

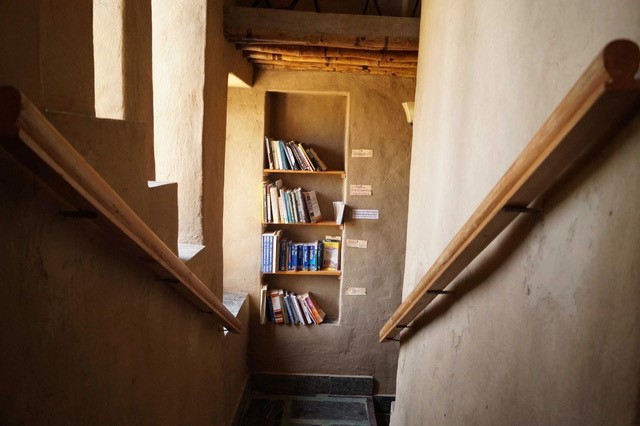

With her artistic background, she switched to architecture and interior design. For her, there was only a medium change to clay, bamboo, slate and river stone.

With her artistic background, she switched to architecture and interior design. For her, there was only a medium change to clay, bamboo, slate and river stone.

During the last three decades, she designed and built more than 15 houses in and around Dharamshala and some other institutions.

During the last three decades, she designed and built more than 15 houses in and around Dharamshala and some other institutions.

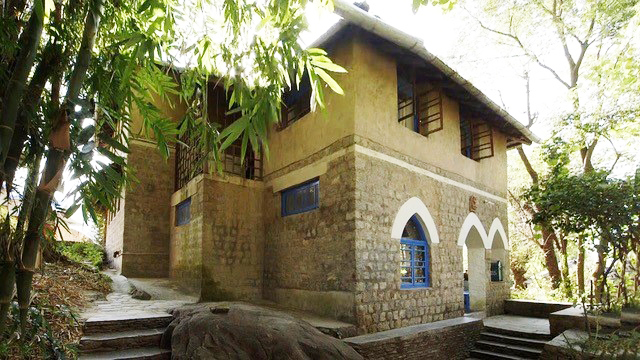

Her buildings seem to grow from the earth and are in perfect harmony with nature. Didi herself explained, “I am very interested in using landscape as a visual and emotional bridge between the built and the natural. Look at the old buildings, they are beautiful in the landscape, and the new ones are at war with it – they say something. So, we conflict with nature, and nature will conflict with us. I imagine a building as growing, like a plant, within a landscape. Landscaping is a key to this thing of marrying the earth to the building.”

Her buildings seem to grow from the earth and are in perfect harmony with nature. Didi herself explained, “I am very interested in using landscape as a visual and emotional bridge between the built and the natural. Look at the old buildings, they are beautiful in the landscape, and the new ones are at war with it – they say something. So, we conflict with nature, and nature will conflict with us. I imagine a building as growing, like a plant, within a landscape. Landscaping is a key to this thing of marrying the earth to the building.”

Didi said, “I would like to emphasize playfulness, imagination, and celebration. By celebrating materials, noticing their qualities, and celebrating them as you put them into a building, celebrating the quality or the plasticity of the mud, and celebrating the inherent, innate and unavoidable qualities of each material. What the slate does to light, and how the materials play within nature. I try to create something as quiet as possible. What works, should just look natural, as if meant to be.”

Didi said, “I would like to emphasize playfulness, imagination, and celebration. By celebrating materials, noticing their qualities, and celebrating them as you put them into a building, celebrating the quality or the plasticity of the mud, and celebrating the inherent, innate and unavoidable qualities of each material. What the slate does to light, and how the materials play within nature. I try to create something as quiet as possible. What works, should just look natural, as if meant to be.”

To create an eco-friendly architecture, Didi invented a unique approach of following the ‘rhythm of the universe’ or the ‘cycles of nature’. She always tried to synchronize the process of construction with the cycles of nature so that the end product is in harmony with environs.

To create an eco-friendly architecture, Didi invented a unique approach of following the ‘rhythm of the universe’ or the ‘cycles of nature’. She always tried to synchronize the process of construction with the cycles of nature so that the end product is in harmony with environs.

Explaining this approach she said, “One of the many things that’s wrong today is that people are not ready to accommodate their lives to the rhythm of the universe. We don’t see the wisdom of nature. Technology should also be consistent with a humanistic agenda of making people comfortable with themselves, with one another and with nature. Eco-sensitive structures need to be built as per the season, whereas cement structures can be built quickly and at any time of the year. One of the problems with contemporary life is losing contact with the cycles of nature. When I take something out of the natural cycle, I think how it affects that cycle, and whether it can be replaced, or reused – earth from an adobe building can be reused in a vegetable garden.”

Explaining this approach she said, “One of the many things that’s wrong today is that people are not ready to accommodate their lives to the rhythm of the universe. We don’t see the wisdom of nature. Technology should also be consistent with a humanistic agenda of making people comfortable with themselves, with one another and with nature. Eco-sensitive structures need to be built as per the season, whereas cement structures can be built quickly and at any time of the year. One of the problems with contemporary life is losing contact with the cycles of nature. When I take something out of the natural cycle, I think how it affects that cycle, and whether it can be replaced, or reused – earth from an adobe building can be reused in a vegetable garden.”

Being an artist originally, Didi had matured the art of handling natural light in the interiors very imaginatively and artistically. An overview of her buildings reveals the emphasis she gives to this vital element of design. For her, the light is the soul of architecture. It highlights the plastic forms, shapes, geometric lines, colors and textures of materials.

Being an artist originally, Didi had matured the art of handling natural light in the interiors very imaginatively and artistically. An overview of her buildings reveals the emphasis she gives to this vital element of design. For her, the light is the soul of architecture. It highlights the plastic forms, shapes, geometric lines, colors and textures of materials.

Didi proved that one could create beautiful, functional spaces without compromising the earth’s resources or disrupting natural cycles. Her innovative use of local materials, her respect for traditional building techniques, and her ability to seamlessly blend structures with their surroundings continue to inspire architects, environmentalists, and artists worldwide.

Didi proved that one could create beautiful, functional spaces without compromising the earth’s resources or disrupting natural cycles. Her innovative use of local materials, her respect for traditional building techniques, and her ability to seamlessly blend structures with their surroundings continue to inspire architects, environmentalists, and artists worldwide.

You can read the original article at hillpost.in

You can read the original article at hillpost.in