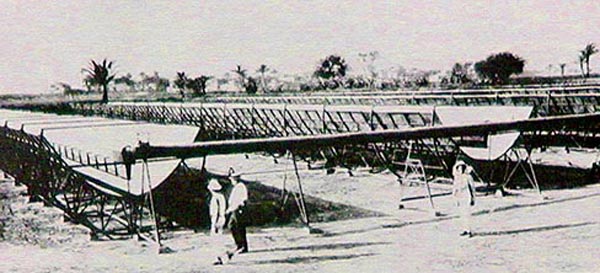

“On a clear, blazing hot day in June of 1913, the cream of British colonial society in Egypt—including journalists, ranking civil servants, and diplomats—gathered in Maadi, a small farming village on the banks of the Nile several miles south of Cairo, for the grand opening of a most unusual irrigation plant. Sipping champagne and snacking on cheese and caviar, mustachioed men in Panama hats and pith helmets and elegant ladies carrying parasols strolled the grounds, marveling at the long, gleaming rows of trough-shaped mirrors concentrating sunlight onto cast-iron boilers running the length of each trough. Heated to just more than 200 degrees Fahrenheit, water in the boilers turned to low-pressure steam to drive a specially designed, 75 horsepower engine. As if by magic, running on nothing more than sunlight, the engine pumped thousands of gallons of water from the Nile, saturating the arid landscape.

After years of honing his technical expertise and preaching the solar gospel, Frank Shuman had in hand a technology he believed capable of convincing not only his financial backers and the editors of Scientific American but the entire world that solar power had arrived as a viable alternative to coal power. And on that June day in 1913, as the sun plant’s specially designed steam engine chugged into action, pumping thousands of gallons of water to dramatic effect, Shuman stood triumphant. Like the celebrated Wright brothers, who only a decade earlier had made real the seemingly impossible dream of human flight, Shuman had finally, it appeared, succeeded where all other solar visionaries had failed. Here, for the first time in history, was a commercial scale solar plant doing useful work previously impossible due to the high cost of coal.

Solar power truly seemed to have crossed a threshold, now standing on the brink of widespread commercial success. Lord Kitchener certainly thought so. Thrilled at having found a cost-effective way to upgrade Egypt’s irrigation system and increase the country’s lucrative cotton crop, Kitchener offered Shuman a 30,000- acre cotton plantation in British Sudan on which to build a much larger version of the solar plant. The German government, whose ambassador to Egypt was among those invited to the Maadi plant’s grand opening, awarded Shuman $200,000 in Deutschmarks to design and construct a solar-powered irrigation system in German-controlled Africa, in the southwest part of the continent. Flush with success, fame, and funds, Shuman envisioned solar power plants on vast scales, going so far as to begin sketching designs for a 20,000 square mile plant in the Sahara desert to generate 270 million horsepower—an amount, he noted, equal to all the fuel burned around the world in 1909.”

More at the source: Renewable Book.com (fascinating bit of history)

This is a brief excerpt from the Renewable Book by author Jeremy Shere. You can learn more about the book here.