The Filipinos believe that man and woman first emerged from the nodes of a bamboo stalk. The Chinese view bamboo as a symbol of their culture and values; it is a symbol of prosperity in Japan and friendship in India.

The plant is native to a wide range of ecosystems – from the hot tropical regions of Indonesia to the cold mountains of Tibet. Across Asia, bamboo has offered itself as a viable construction material owing to its strength, flexibility, and easy availability. Now, it struggles to compete with man-made materials like cement and steel to meet immediate issues of urbanization.

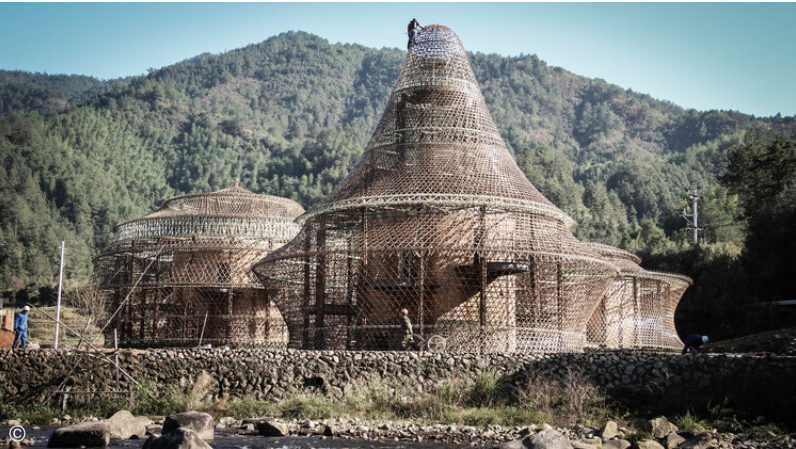

Unlike fabricated materials, the naturally-grown plant comes in a variety of shapes and sizes, making it difficult to generalize norms and standards around construction methods. Restrictive building codes and an inability to grade the material also hinder the adoption of bamboo. Construction techniques require skill, especially when used in conjunction with steel, concrete, or glass.

Bamboo is proving its worth as a sustainable material.. Its strongest assets are carbon sequestration and helping to clean the environment. Early Asian bamboo settlements were always built in harmony with local ecosystems, resulting in a balanced built environment. Contemporary bamboo structures are often initiated for more aesthetically-inclined motives, with eco-friendliness as an added advantage.

Population giants like China, India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia are faced with the responsibility of developing housing and infrastructure at exponential rates. And there is a quest to rediscover cultural identity in the built landscape. Asian cities can reach into their pasts to solve urban crises with vernacular technologies and local materials.

The plant can be harvested in 3-5 years while traditional sources of timber would require 10x more time. In Nepal and Bangladesh, bamboo structures have quickly been erected and reproduced as disaster relief shelters. Being locally available, strong, and versatile, bamboo is a practical low-cost construction material for this region. It serves as a cost-efficient alternative to timber, offering similar if not better structural qualities. The growth and production of bamboo place power back in the communities’ hands, often creating circular economies around its processes.

Being a naturally grown construction material with little refinement processes, bamboo is great for the planet. The more it is harvested, the faster it grows, providing wildlife habitat, restoring watersheds, and supporting indigenous communities.

A gap is found in vernacular knowledge when it comes to high-rise buildings, a common stereotype of developed cities. Tall structures provide a practical way of de-congesting urban sprawl. Bamboo skyscrapers could be a reality by using the material in combination with other materials.

The joints of the structure are most important to secure the building and are often reinforced with steel. Triangulation – the arrangement of bamboo stalks in triangles for structural optimization – is another technique that allows the grass to tower into the sky. Experimentation with light-weight 3D-printed bamboo structures opens up opportunities for more widespread use of the material.

A renaissance of bamboo architecture in Asia is underway. It is time Asian architects reinterpret the meaning of “developed” and use bamboo to claim their place as important contributors to the world. With the promotion of advanced technology and experimentation in bamboo construction, experimental structures are finding homes in growing Asian cities. The material reminds Asians of their roots and their deep connection with the natural world, paving way for sustainably-advanced human habitats of the future.

You can read the original article at www.archdaily.com