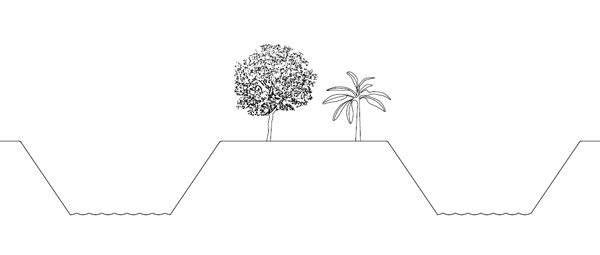

A basic tenet of permaculture is for everything to have more than one use. In the example shown here, instead of having a fish pond separate from an orchard, agroforest or forest garden the two are integrated for increased efficiency. I’m starting to see this type of agricultural practice here and there. I imagine the idea sprang from growing fruit trees next to a lake or pond. If the surrounding land is about 6’-8’ (2m) above the water table, the tree roots can readily reach the water so no irrigation is needed after the first few years. There are lots of possibilities with this basic concept. The ratio of land to fish pond can be changed depending on what you want to produce the most of. The height can be adjusted according to the type of trees. And the overall size and shape can be adjusted to fit your homestead or farm.

The system described above is one example of integrated farming (or permaculture, depending how you categorize things).

“Integrated farming or integrated production is a commonly and broadly used word to explain a more integrated approach to farming as compared to existing monoculture approaches. It refers to agricultural systems that integrate livestock and crop production and may sometimes be known as Integrated Biosystems.

While not often considered as part of the permaculture movement Integrated Farming is a similar “whole systems approach” to agriculture. There have been efforts to link the two together such as at the 2007 International Permaculture Conference in Brazil. Agro-ecology (which was developed at University of California Santa Cruz) and Bio-dynamic farming also describe similar integrated approaches.

Examples include:

– “pig tractor” systems where the animals are confined in crop fields well prior to planting and “plow” the field by digging for roots

– poultry used in orchards or vineyards after harvest to clear rotten fruit and weeds while fertilizing the soil

– cattle or other livestock allowed to graze cover crops between crops on farms that contain both cropland and pasture (or where transhumance is employed)

– Water based agricultural systems that provide way for effective and efficient recycling of farm nutrients producing fuel, fertilizer and a compost tea/mineralized irrigation water in the process.”

We have a “be nice” comment policy here. Rude, insulting and off topic comments will be deleted. Why waste your time?

Look through the 1,600+ posts and over 9,000 comments and what do you see? No spam, no rude comments. We plan to keep it that way.

Before posting, ask yourself: “Will this be of interest or benefit to readers?”

Videos of children gardening. = What could possibly be nicer than that?

Helping readers see that gardening need not be complex if they choose to keep it simple?

In my estimation would be extremely interesting and beneficial to readers.

You totally missed the point. Reread the part about growing sizable gardens that make a significant contribution toward your food supply. Something like that. We’re not talking about 10’x10′ children’s gardens with radishes and lettuce. (But that is a good way to get kids started, by the way.) We’re talking about people who want to start a homestead or a sizable garden to shift away from buying store bought food. Talk to anyone with a sizable garden and they’ll tell you about all the challenges involved (insects, plant diseases, constant weeds, late frosts, gophers, you name it). Gardening is not quick and easy by any means.

Here’s one of probably hundreds of stories I could find for you if you’re still not convinced.

http://permaculturenews.org/2012/01/20/swale-fail/

Humans don’t have to understand all the complexity to be successful. Nature will take care of that for us, if we choose to allow it to do so.

Gardening can be as simple as putting seeds into the soil, and standing back to allow nature to do the rest. At it’s core. That is the best garden. That is NATURAL gardening, and this blog is titled, “Naturalbuildingblog.com”. It seems appropriate for this blog to explore the most natural ways of building a garden.

I submit that Nature is far better at building gardens than man can ever be. The best man can ever hope to accomplish is to give nature a gentle helping hand here and there. That activity need not be complex.

Anyone can make it complicated if they choose to. Someone can stress themselves out reading countless texts, many of which contradict each other. Someone can try to engineer their garden and draw up plans for it like an architect draws plans for a house.

There is another way. The Native American Indians excelled at it. Contrary to most common perceptions, the Native American Indians were not simple hunters and gathers. They also gardened and farmed, but not in the destructive intrusive ways most gardens are created today.

Ancient Native Americans observed nature very carefully. They built their entire belief system around it. When they found a food source growing in a certain area, they would scatter more seeds like that around in that area, and similar areas. Then they waited, watched, and observed. (Just like the fundamental principles of Permaculture teach… observation and duplication is hardly anything new.) They attempted to return to the soil that which they took from it. For them it was, (and for many still is) a fundamental belief system for how to live life.

There is a reason that Chestnut trees once overwhelmed the American Landscape.

The chestnut had many valuable properties. Its wood was easily split, easily worked, and highly rot-resistant. Tannins from the bark and heartwood were the best available for tanning heavy leathers. A consistent production of annual nut crops, in contrast to the sporadic acorn crops of oak, made the chestnut an important food source for man and wildlife. Even-aged stands at village sites suggest that chestnut was planted and cultured by Native Americans.

This ancient predecessor to Permaculture was practiced all across the continent in ancient times. (Don’t get me started about Europeans importing non-native species and intruding blight which has all but wiped out Naive Chestnuts.)

I’m not trying to say everyone should abandon their religion to worship as Native Americans did. However, we can still learn from the gardening and farming practices Ancient Native Americans practiced. (As a side point, this topic of how Native Americans practiced an ancient form of Permaculture would make for an outstanding blog post.)

My point is that it is not complicated to simply to plant seeds and observe what happens. Replicate what works well.

This does not have to be intimidating. It can be practiced on a small scale, or a large scale.

Just as it is appropriate for an individual to build a shed to gain experience before building a house, it is appropriate for individuals to tend a small garden before attempting a huge project. That doesn’t mean that someone must finish a Doctoral Dissertation to be very successful at building a magnificent home or a garden that provides more than enough food for a family, a community, or even large populations to eat. It simply requires that someone be willing to observe what works where they are, and build on that.

Pest problems are part of nature. We humans have decided that they are a problem. Perhaps it is time to change that perspective.

Perhaps those pest problems are nature’s way of telling us that we are trying to make our gardens too complicated? Perhaps those pest problems are an indication that our complicated efforts requiring so much human effort are not the best way?

Perhaps the solution to pest problems is to treat pest problems as nature telling us to stop trying to impose our rules on natures’ systems.

KISS principle.

Pest problems just mean:

“Nature wants something else planted here.”

“Nature wants a wider variety of plants here so that if one type of plant is attacked by pests, there are multitudes of other kinds of plants to provide food for us.”

Less monoculturing, more polyculturing. Pests are nature’s messengers telling us that, if we only bother to listen.

Battling pests means you are fighting nature. Try listening.

Look around your natural environment for plants that can privide human food that can handle the local pests.

Simple Solutions to complex situations. It’s all about staying calm, and observing.

I suggest Nature is the best garden builder. We humans should be simple helping hands. The more we try to complicate it, the more we will struggle to succeed.

[edited for brevity]

I forgot to post a link to the source of the italicized quote about Native American Indians cultivating Chestnut Trees.

Here is the link.

http://www.dof.virginia.gov/research/chestnut-amer-hist-rest-in-va.htm

My apologies.

It’s possible, using a mature aquaculture pond (one with a good population of fish) to grow hydroponicly, using floating islands/mats that sit right on top of the water. These mats would contain enough soil or pots filled with soil so that the bottom just rests in the water. Nutrients would be drawn from the water via the roots. The soil would have to be innoculated with benificial bacteria which would convert the ammonia given off by the fish in the form of urine and feces into nitrites. Other bacteria would convert the nitrites into nitrates, which are readily absorbed by the plant roots. These roots in turn purify the water, which is then reused by the fish.

Simple aquaponics.

Good idea, Paul. This reminds me of the floating gardens in Mexico City called chinampas. The floating gardens are built with soil on top of juniper rafts.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xochimilco

This got me thinking of how to apply this idea to my area. There are thousands of small fish ponds and lakes here, yet no one to my knowledge makes use of floating gardens. Maybe because it’s easier and simpler to grow things on land? Or maybe locals just haven’t thought of it yet. Floating gardens would eliminate irrigation in the dry season (almost 7 months) and utilize unused space (the water surface). The plants and fish would benefit each other as Paul is describing. Also, the floating gardens would cool the water temperature and attract a bunch of additional insects. I need to look into this more. Sounds like it this idea has very good potential.

Also note, you could have an orchard or forest garden as explained in this blog post and grow floating gardens. That could double food production!

Now I need to figure out what materials will work best here. (I don’t want to use plastic bottles.) There is a cane used to make boats called totoro reed that should work nicely. Not sure how many years it would last. http://www.lonelyplanet.com/peru/lake-titicaca/images/fisherman-lake-titicaca$2019-1

Thank you Paul and Dr. Geiger. THIS seems to fit a much better idea of using the water instead of an island. Washington state gets alot of rain but, what most people don’t know is there’s a water shortage. My thought IS to secure that water for drinking and to grow food together. THIS idea is so much better. It retains more water plus it gives me my garden. I hope you gentlemen have detailed ideas on how to proceed in making this floating garden. I really would appreciate it. It’s a great idea.

See today’s blog post on floating islands. One problem is getting permission to build a retaining pond. Check your local regulations. Bizarre as it sounds, collecting roof water and water runoff from your land is against the law in many areas. Of course countless thousands of people don’t follow these laws, but that’s another topic.

You’re right about collecting water but, here it’s encouraged so that’s good. I have 4 retaing ponds just over the hill from where I live that collects rain runoff and they use it for the vegetation around the area. As far as the retaining pond…..I’ll do it anyway disregarding WHAT they would say but, I “THINK” they wouldn’t have a problem with it. Remember I’m going WAY off grid. If it seems illogical….I won’t buy into it.

As explained in today’s blog post on floating islands, there are numerous ways of building them. One method doesn’t use any soil. Some use rot resistant wood such as cedar or juniper branches. Some use cane or bamboo. I’ve also seen commercially available plastic floatation devices, but I didn’t report on this technique because the plastic will likely leach chemicals into the water. (It’s difficult to avoid plastic completely, but I like to eliminate it when possible.) Using natural materials is free and safe.

Thanks Dr. but, just “HOW” would you build such a structure??

Are you talking about floating gardens? As usual, use whatever you have locally and what makes sense. Some people have loads of juniper/cedar, some have bamboo. Maybe make 2-3 types and see what works best. Start small and expand later once you learn the most effective methods. I love doing little low cost experiments like this. Have fun and let us know the results.

Okay..gotcha’ I think I was reading too much into the construction of the thing. I tried to make it too complicated. I had one of those “DUH…” moments. Maybe that’s just a trait of Irish American men sometimes…

This is one reason I love blogging. I’ve known about floating gardens in Mexico and Myanmar (http://www.thailex.asia/THAILEX/THAILEXENG/lexicon/floating%20garden%20agriculture.htm) and Cambodia (http://www.livelearn.org/projects/floating-gardens-project) for years, but the concept was sort of an abstract thing from history. Paul’s suggestion has jolted me into researching this more. It’s so simple!!! Why aren’t more people doing this? Irrigation is a big expense and time waster.

Related: Thousands of farmers here dig fish ponds to diversify their income and produce fish for their own consumption. The ponds also serve as a reservoir for use in the dry season. There are rural cooperatives that dig the ponds at very low cost. The excavated soil is trucked away to build roads and raise building sites above the floodplain.

Update: I forgot about the floating gardens in Bangladesh.

http://practicalaction.org/floating-gardens This sounds good enough for a blog post.

The reason I originally asked the question about planting a garden on an island is I plan to dig out a chunk of land that has a small stream running through it to create a pond or better yet a small fresh water reservoir. And, I thought that maybe, after reading this, that I’d leave a small island in the middle with a cross walk and grow vegetables. If this isn’t truly feasible then I’ll stick to my square foot gardening where I can have it closer to the house and hand water. I was thinking that maybe I wouldn’t have to water at all and, the plants wouldn’t get saturated. That’s all.

Streams often rise a lot during the spring runoff and that could put your plants at risk. Better in my opinion to put a pond off to the side and have it available for irrigation. Having the plants near the house is a big plus, especially if you’re near an area with wild animals. Deer, skunks, coons, etc. love to raid homesteads.

Mmmmmm….good point. Hadn’t taken that into consideration.

Am I incorrect to think that a regular garden wouldn’t work for this kind of set up? That would be real good if you never had to water your garden

You could do this with a regular garden and ample water if you decrease the distance between the plants and water and get the distance just right. Too low and you’d sink in mud. Too high and the roots wouldn’t reach the water. One option is to grow only deep rooted vegetables. I think in general the presence of water just below the surface would stimulate plant growth. The roots would sense the water and grow like crazy.

Another option is to raise the land a bit higher and use a small pump such as a bicycle or treadle pump for irrigation. https://naturalbuildingblog.siterubix.com/cottage-industry-appropriate-technology/

We’re still trying to figure out what this is commonly called so the subject can be researched more thoroughly.

It all depends on your climate and your choice of plants in your garden.

Many gardens grew for thousands of years before man learned to pump water. Many non-irrigated gardens still produce prolifically today.

The key is to find the right balance between that water that is naturally available at your garden site, the plants that are using the water, and the growth medium.

As general rule of thumb, select a garden site that will naturally collect water from the surrounding terrain, but not get flooded or washed away. Avoid tilling the soil. Use as much compost as possible. Mulch as much as possible.

In many ways, the best way to store water is not in open ponds. You lose a lot to evaporation. The best way to store water is in organic matter buried underneath your garden and insulated and protected from evaporation by a very thick layer of mulch.

Then select plants that can handle whatever water is available, and select plants that will send down deep enough roots to get to that water, especially during the dry season.

In case you haven’t noticed, what is being described is a forest ecosystem. Check out the forest in the high desert of California. Not much rain, but dig down in the forest soil, and you’ll consistently find moisture available to plant roots. It’s not magic. It’s nature’s system at work. Don’t fight it. Duplicate it and work with it.

Good points. Work with nature. Use what works best in your area. The system I’m describing is not suited to every area. It’s just one of many different permaculture/integrated farming techniques. There are hundreds of such techniques one could use. It takes a lot of time and effort to learn what works best in a particular area.

Not as much time as many individuals might think.

All one needs to do is be very observant of nature around you.

If ever there was an expert on this topic, it’s Brad Lancaster, who has been discussed previously on this blog. Here are his recommendations. Carroll was asking about creating an non-irrigated garden. Brad Lancaster is the expert that will tell her exactly how to accomplish that.

Here is an interview where Brad discusses how to select the proper plants.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ib0drunwTw

That was part 3 of a YouTube series.

Here are parts 1 and 2.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2iQ-FBAmvBw

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xS-XQUkSGvU

As long as someone follows Brad’s guidance, they should find a great deal of success very quickly.

It can take years to learn all the ins and outs of gardening. Sure, you could learn some key basics in a few days that will get you started. But it’s far from simple to learn all about how to control insects, what plants grow best together (companion planting), optimum planting times, pruning, fertilizing, seed saving, on and on. Many gardens flop. I don’t feel like getting into a lengthy debate about this. If you think it’s ‘easy’ then that’s fine. But I don’t want to send the wrong message to those just starting out. Gardening is a lot of work and you’ll almost certainly make lots of mistakes. That’s just the way it is. Even with a degree in horticulture (like my friend) you’ll face lots of problems: the cows and goats will break through the fence, swarms of grasshoppers will be attracted to the moist delicious vegetation, the pH of the water may cause problems, flash flooding may wash away your topsoil, each kind of plant has a whole set of requirements and different pests that try to wipe it out, and on and on it goes. You’ll even get conflicting information from horticulture experts. I know. It just happened to us the other day.

One of many examples I could give: Some local farmers (girlfriend’s parents) severely damaged their rubber trees by overfertilizing and watering during the dry season. This caused the trees to grow too fast and now the branches are breaking off. This incident shows how even lifelong farmers make mistakes.

Brad Lancaster is great, but he only addresses one type of environment. Gardeners have to learn how to garden in their environment, which will likely be very different than what he talks about.

Again, please no lengthy comments.

If someone wants to build the Taj Mahal, it will be difficult and take a very long time.

If someone wants to build a small shed. It can be built in a weekend.

Just because someone doesn’t learn everything there is to know about a topic doesn’t mean that they cannot be highly successful at taking on small challenges.

Gardening is a very broad topic, just as architecture is.

Building a food forest over dozens of acres is apt to be a lifelong project where someone never learns everything.

That doesn’t mean that building a small family garden of a hundred square feet should intimidate anyone. It doesn’t HAVE to be that hard.

Perspective. Setting appropriate goals for each individual to match their skillset. Enjoying the successes and shrugging off the failures. These are all life lessons that gardening tends to teach.

Well… that and humility. Mother nature always has a tendency to keep us all humble.

I’m talking about gardens that are large enough to produce a decent amount of food, which will help you save money and avoid junk in the food. Like we recommend with natural building, start small and build up gradually to minimize pain and losses.

Seems to me that the important factor in this particular discussion is what the person who posed the question that started this discussion wants. What you or I may personally desire is immaterial to that point.

Carroll asked about a self watering garden. My response was to suggest looking into the principles promoted by Brad Lancaster as the way to accomplish that. I still think that is the fastest easiest and most appropriate way to accomplish the goal she stated. Owen, if you think a pond is a better method to support Carroll’s goal, then I encourage you to give reasons why. I’d love to read them.

Now… ponds and aquaculture mixed with agroforestry is a worthwhile concept as well, but in my opinion is over complicated if someone is only looking for a self watering garden, and not for fish or trees.

I don’t expect Carroll to necessarily want the exact same things I want, so I was trying to answer her question.

I’m just throwing out ideas to try and help. And like I said, everyone has to figure out what works best in their area. What works great in one area may not work in another. Gardening is complex.

It is a extremely common practice to place a chicken coup and chicken run underneath a fruit bearing tree, such as a mulberry. The fruit that drops from the tree feeds the chickens. It’s a wonderful integrated system.

Why couldn’t this apply to fish as well as chickens?

I wonder what trees might shed seeds or fruits that would be good fish food? Numerous trees shed all kinds of floating, spinning, seeds. It probably depends greatly on the species of fish, but the trees selected shed seeds, or other debris (leaves, bird poo, insect larve from tree nests, etc) that the fish like to eat, it could be an excellent integrated system.

The one potential problem I see with this concept of expecting a pond to irrigate trees is when someone attempts to create an artificial pond. Especially when they used a pond liner to hold in the water. If the tree roots penetrate the liner to get access to the water, then the pond may be compromised. If the tree roots do not penentrate the liner, will the tree get enough water?

If a pond is lined, I may make more sense to place the trees around the spillway and runoff channel.

Naturally occuring ponds and unlined ponds would not have the same concerns.

Fun mental exercize.

Yes, there are lots of possibilities. I’m just showing the basic fruit tree/fish pond combination to convey the main idea. You could add lots of other things. Chicken tractors are common. You could make islands to help protect chickens, turkeys, etc. I would plant a forest garden not just trees. You could make multiple ponds with raised growing areas between so there’s a pond for each stage of fish production. Add a gate so fish can swim to the next pond when they’re at the appropriate stage.

I’ve only just begun learning about this system. Not sure what types of trees are best.

I know a guy who’s having good success with a strobe light(?) and black light over the pond. The strobe light is high on a pole and draws insects from far away. The black light is placed down low facing the water. Insects see the reflections and dive into the water where the fish are waiting for them. This saves a lot of store bought fish food and is probably healthier.

I haven’t heard of anyone using a pond liner. People are doing it in our area to reduce irrigation work in the long summers (about 7 months with almost no rain).

Look up “wicking well” technology. This was developed for drought-ravaged farm lands in Australia.

Thanks. I’m looking now. All I see so far are small planters that use wicking wells. I’ll keep looking.

I’m not sure what to call this farming technique. It’s relatively new to me and I’ve been unable to find details on the Internet. Does anyone know of a better name than what’s shown in the title? Knowing the standard name would facilitate further research.