Barn raising has long served as a cultural way to extol virtues of mutual aid and premodern communitarianism, a symbolic reference for an event where neighbors come together to build together. But instead of an origin story of American pastoralism or a romanticized view of country life, barn raising is more instructive as a collective construction practice that challenges notions of property, relying on systems of exchange built on favors and community over individualism and profit.

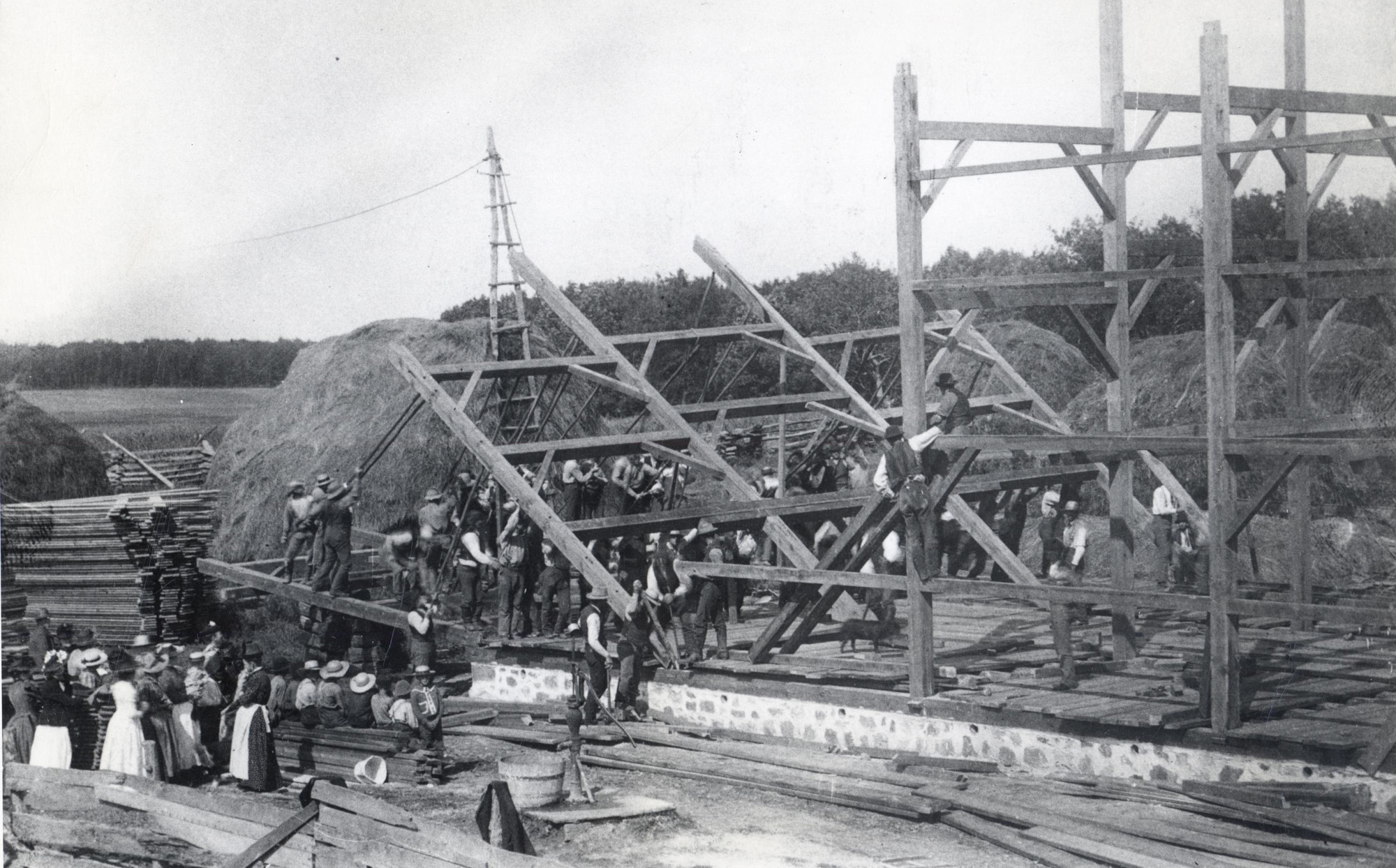

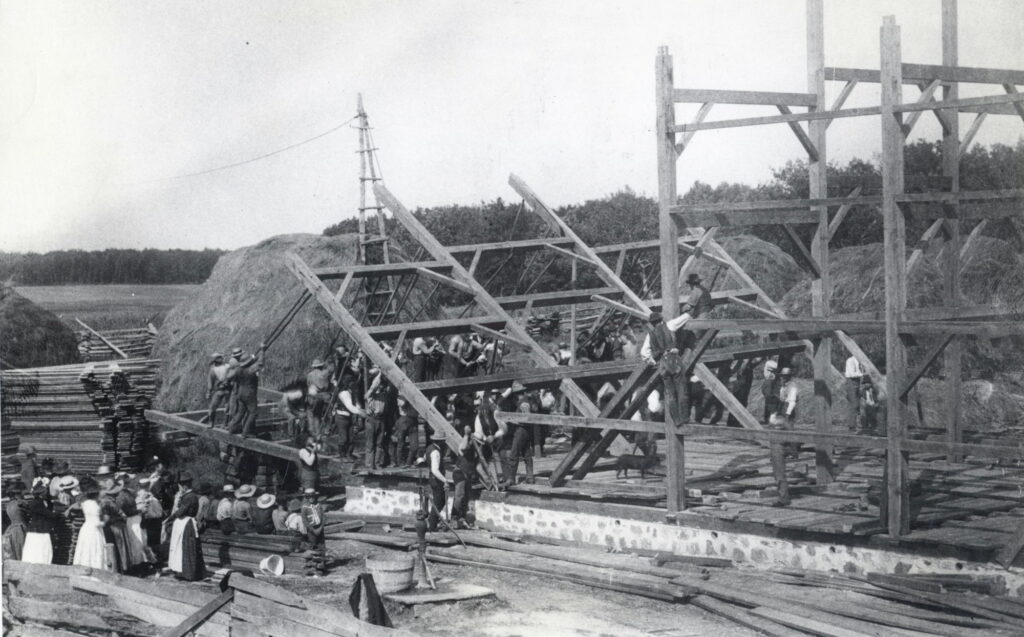

Historic barn raisings relied on tight-knit, often exclusionary self-determined communities and were overwhelmingly patriarchal. The spectacle of community in action was limited to those whose presence affirmed a narrow ideal of who belonged in public. Men built, women cooked, children watched. To participate was to perform one’s role in the community, and those attending were always counted. “Over 100 assisted” at a raising for “progressive farmer” Charlie Stout, “one hundred and thirty persons took dinner at Mr. Eckles’s,” while a smaller crew of thirty-six raised a frame in Rockford, Illinois. Headcounts functioned as a measure of social currency, proof of community standing, and were a regular appearance in nineteenth-century newspaper articles and county agricultural columns.

Accidents were just as common as the raisings themselves: “a heavy bent fell in a heap, killing one man instantly and fatally injuring four others.” Another collapse “killed seven men on the spot.” Despite the constancy of these stories (some of which were likely hyperbole), neighbors still showed up, because absence counted too.

Accidents were just as common as the raisings themselves: “a heavy bent fell in a heap, killing one man instantly and fatally injuring four others.” Another collapse “killed seven men on the spot.” Despite the constancy of these stories (some of which were likely hyperbole), neighbors still showed up, because absence counted too.

Meals were equally structural, expected, and scrutinized: “The feast prepared upon these occasions, is regarded as the substantial feature of the day’s program.” At one raising, a baker brought “100 loaves of bread and 400 rusks to feed the many that were expected.”

These accounts include a remarkable amount of technical detail for a general audience. One, for example, describes how “while standing upon an upper beam endeavoring to fit the purlin plate to its place, the post intended to support this plate slipped from its fastening and fell.” Mortises, tenons, plates, and bents appeared in print without explanation, but with the same fluency as elections and markets, suggesting a common knowledge important enough in everyday life that a reader would be erudite in the language of construction. Today, architecture has given up on that kind of public literacy.

Taken together, the accounts reveal a shared practice structured as much by expectation and obligation, as by risk and recognition. Raisings, in this sense, reveal the dependencies that exist in all forms of collective work. And for this reason, they are sites to redesign the social infrastructure of the built environment.

While participation was highly visible in nineteenth-century raisings, today it’s diffused into economies of labor, material, infrastructure, and globalization. In practice it’s fundamental to building, but architecture has rarely positioned participation as such: from people at oil fields fueling petrochemical plants to millworkers sawing timber, long-haul truckers moving rebar, masons laying brick, carpenters framing walls, factory workers pressing tiles, electricians, plumbers, roofers, tile setters, drywall crews, finish carpenters, sales reps, inspectors, sanitation workers, and maintenance crews—all play a part. Architecture is dependent on bodies whose contributions are rarely counted and routinely anonymized.

You can read the original article at www.e-flux.com