Ronald Rael, practices architecture and holds a chair at the University of California, Berkeley. His work often connects indigenous and traditional material practices with contemporary technologies.

Ronald Rael, practices architecture and holds a chair at the University of California, Berkeley. His work often connects indigenous and traditional material practices with contemporary technologies.

In an interview with ArchDaily, Rael shared some reflections on the evolution of his work, the role of technology in the development of architecture, its social utility, and the role of materials in it.

Considering your broad practice—which ranges from materials and technology to social studies—, what is the common thread running through your current work?

Ronald Rael: One thing that I think is a common thread through my work today is that I’m very interested in how the material is related not only to construction but also to its material culture. I like to think about the broader culture that material possesses and its social and economic impact. My focus now is related to a particular place, and that is the current borderlands between the United States and Mexico.

Ronald Rael: One thing that I think is a common thread through my work today is that I’m very interested in how the material is related not only to construction but also to its material culture. I like to think about the broader culture that material possesses and its social and economic impact. My focus now is related to a particular place, and that is the current borderlands between the United States and Mexico.

Looking back a few decades, the definition of architecture today is much broader, extending beyond creating buildings or delimiting spaces. Do you believe professional reinvention may be necessary in today’s world?

I do think it’s possible for people who have architectural training to do more things in the world. And they’re very equipped to do anything from technology to construction, to thinking about social issues. So I think general design is very broad and has a lot of applications and that is the beauty of architecture.

I do think it’s possible for people who have architectural training to do more things in the world. And they’re very equipped to do anything from technology to construction, to thinking about social issues. So I think general design is very broad and has a lot of applications and that is the beauty of architecture.

It seems that technology, sustainability, and social utility have emerged as central themes. What areas do you think students, architects, and designers should prioritize in the current landscape?

Architecture has been a white male-dominated profession, so some students entering into that world can find a lot of challenges in finding their place within that world that’s already very well-established. Students must recognize where did they come from? What are the issues and challenges that they had? And how might that apply to them reimagining the future of a profession where you’re changing the world.

Architecture has been a white male-dominated profession, so some students entering into that world can find a lot of challenges in finding their place within that world that’s already very well-established. Students must recognize where did they come from? What are the issues and challenges that they had? And how might that apply to them reimagining the future of a profession where you’re changing the world.

With innovative technologies, we’re seeing significant shifts in design as traditional limitations fade. This opens up a realm of experimentation that could be a game-changer. How do you see these new possibilities evolving, and what role will experimentation play?

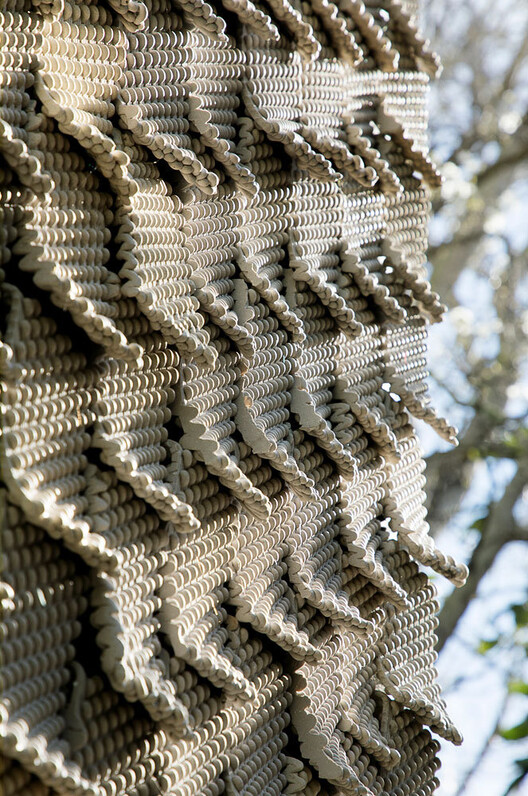

I really believe in that old Marshall McLuhan saying that “the medium is the message.” So, if you’re drawing with a T-square, you’re likely to design something influenced by that tool. If you’re drawing with a computer, utilizing the incredible tools available today—robots and AI—image production has become extremely influential.

I really believe in that old Marshall McLuhan saying that “the medium is the message.” So, if you’re drawing with a T-square, you’re likely to design something influenced by that tool. If you’re drawing with a computer, utilizing the incredible tools available today—robots and AI—image production has become extremely influential.

On the manufacturing side, do you foresee a change in the trend of material production? Will it move closer to a slow architecture or will mass production remain the baseline?

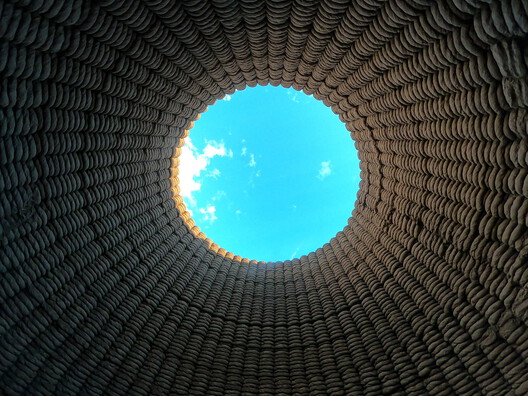

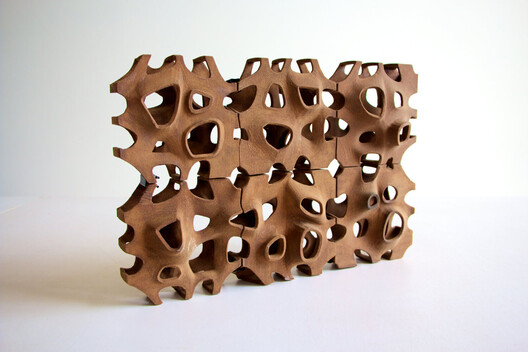

Concrete remains the most widely used material on the planet. While it used to be earth—a carbon-zero material—, our construction demands have evolved with taller buildings and growing populations. I do believe we can draw from the past and traditional craft technologies to incorporate them into modern architectural and construction practices. Over the past 150 years, there’s been a disregard for these craft practices, leading to the loss of many traditional techniques in wood, stone, earth, and textiles. I think there are opportunities now, not only to reintroduce these practices but also to reinvent them using modern technologies.

Concrete remains the most widely used material on the planet. While it used to be earth—a carbon-zero material—, our construction demands have evolved with taller buildings and growing populations. I do believe we can draw from the past and traditional craft technologies to incorporate them into modern architectural and construction practices. Over the past 150 years, there’s been a disregard for these craft practices, leading to the loss of many traditional techniques in wood, stone, earth, and textiles. I think there are opportunities now, not only to reintroduce these practices but also to reinvent them using modern technologies.

To conclude, some global challenges on the horizon could be daunting. What do you think is the potential of architecture and technology for the coming decades?

I think something that would have the potential for changing architecture is to think about how the materials we use are actually reparative or restorative; that they’re not damaging. Can we find materials that heal rather than destroy, or that contribute rather than take away? I think that’s the direction earthen materials are headed.

I think something that would have the potential for changing architecture is to think about how the materials we use are actually reparative or restorative; that they’re not damaging. Can we find materials that heal rather than destroy, or that contribute rather than take away? I think that’s the direction earthen materials are headed.

I think the way forward is actually taking a break, slowing down, looking back, and remembering what was good and bringing it forward. We need to do it in a way where it responds to our 21st-century way of life, though; we can’t be romantic and say we’re going to live like we did 10,000 years ago. How can we respond to today? That’s important.

I think the way forward is actually taking a break, slowing down, looking back, and remembering what was good and bringing it forward. We need to do it in a way where it responds to our 21st-century way of life, though; we can’t be romantic and say we’re going to live like we did 10,000 years ago. How can we respond to today? That’s important.

You can read the original article at www.archdaily.com