Jaya Thursfield and his Japanese-born wife, Chihiro, moved to Japan from London in 2017 with their two young sons and a dream of buying a home with a big yard. What they found was a house that had been abandoned about seven years earlier — one of the millions of vacant houses known as akiya, Japanese for “empty house” — throughout the country. Slightly curving eaves were much higher off the ground than those of most houses. The entrance hall had its own gabled tile roof. The 2,700-square-foot house looked more like a Buddhist temple than a farmhouse because it had been built by a temple architect in 1989.

“We would never have been able to afford a house of this quality and size if it wasn’t an akiya,” Chihiro said. “And while many Japanese don’t like used homes, foreigners see a house that is cheap and are more willing to reuse and renovate to their tastes and budget.”

“We would never have been able to afford a house of this quality and size if it wasn’t an akiya,” Chihiro said. “And while many Japanese don’t like used homes, foreigners see a house that is cheap and are more willing to reuse and renovate to their tastes and budget.”As Japan’s population shrinks and more properties go unclaimed, an emerging segment of buyers, feeling less tethered to cities, is seeking out rural architecture in need of some love. The most recent government data, from the 2018 Housing and Land survey, reported about 8.5 million akiya across the country — roughly 14 percent of the country’s overall housing stock — but observers say there are many more today.

The Thursfields’ house, about 45 minutes from central Tokyo, had been deserted after the previous owner’s family refused to inherit it upon the owner’s death. The local municipality took it over and put it up for auction with a 5 million yen ($38,000) minimum bid, but it failed to sell.

The Thursfields’ house, about 45 minutes from central Tokyo, had been deserted after the previous owner’s family refused to inherit it upon the owner’s death. The local municipality took it over and put it up for auction with a 5 million yen ($38,000) minimum bid, but it failed to sell.When it landed on the block again, Jaya decided to try his luck. After giving the house a quick inspection with an architect friend and finding no major issues despite the years of neglect, he nabbed the house for 3 million yen, about $23,000.

Because the value of a house in Japan typically decreases over time until it is worthless, with only the land retaining value, many buyers seek to demolish a neglected house and start again. “There was no way we wanted to knock it down and build something new. It was too beautiful. So we decided to renovate instead,” Jaya said. “I’ve always been someone who likes to jump in the deep end, take a few risks, and learn new things, so I was confident that we would manage somehow.”

Because the value of a house in Japan typically decreases over time until it is worthless, with only the land retaining value, many buyers seek to demolish a neglected house and start again. “There was no way we wanted to knock it down and build something new. It was too beautiful. So we decided to renovate instead,” Jaya said. “I’ve always been someone who likes to jump in the deep end, take a few risks, and learn new things, so I was confident that we would manage somehow.” Since buying the farmhouse, the couple have spent about $150,000 on renovations, and there’s more to do. Mr. Thursfield has documented the project on YouTube.

Since buying the farmhouse, the couple have spent about $150,000 on renovations, and there’s more to do. Mr. Thursfield has documented the project on YouTube.“Poorly maintained akiya can mar the scenery as well as endanger residents’ lives and property if they collapse,” said a city official in Sakata, along the west coast, where heavy snowfall can damage unattended structures. “We’re partly subsidizing demolitions, collecting neighborhood association reports on akiya, and trying to make owners aware of the problem by holding briefings.

In many cases, the parents die without making clear their wishes regarding the family home, or they develop dementia and find it difficult to discuss these things. In such cases, the children may feel guilty about getting rid of the family home, and may often choose to leave it unoccupied.”

In many cases, the parents die without making clear their wishes regarding the family home, or they develop dementia and find it difficult to discuss these things. In such cases, the children may feel guilty about getting rid of the family home, and may often choose to leave it unoccupied.”The government has approved a plan by the city of Kyoto, where inventory is tight yet some 15,000 houses sit empty, to tax the owners of those empty homes — a first in Japan.

Akiya are increasingly seen not just as a threat to suburban and rural markets, but to the emotional health of the country, sparking family disputes over inherited properties. That, in turn, has led to a cottage industry of akiya consultants who act as a counselors for squabbling relatives, often urging them to act before their properties become a lost cause.

Municipalities across Japan are also compiling listings of vacant houses for sale or rent. Known as “akiya banks,” they are often bare-bones web pages with a few underwhelming photos. Some have partnered with private-sector companies like At Home, which currently lists akiya in 658 of Japan’s 1,741 municipalities.

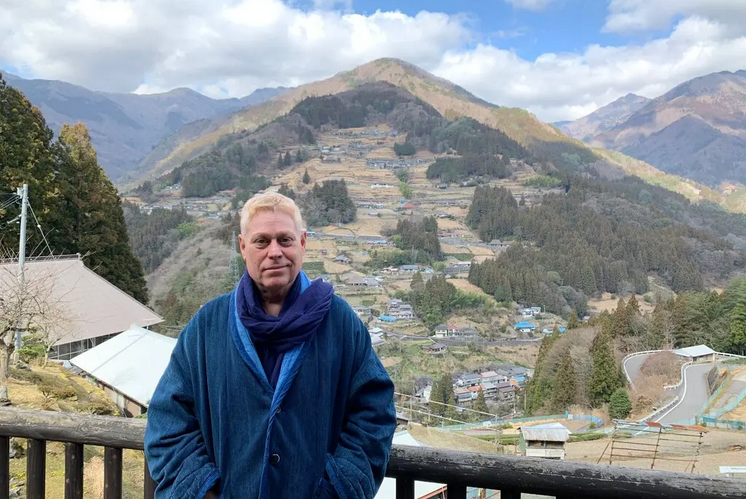

Alex Kerr, an author and Japanologist originally from Maryland, became an akiya owner in 1973 when he acquired an abandoned country house in the mountains of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, for $1,800. The thatched-roof house is about 300 years old. Inside, it’s a shadowy space of polished wood floorboards, a large sunken hearth and giant overhead rafters wreathed in smoke.

Alex Kerr, an author and Japanologist originally from Maryland, became an akiya owner in 1973 when he acquired an abandoned country house in the mountains of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, for $1,800. The thatched-roof house is about 300 years old. Inside, it’s a shadowy space of polished wood floorboards, a large sunken hearth and giant overhead rafters wreathed in smoke. Mr. Kerr is the first to admit that akiya can be money pits. He has spent decades and roughly $700,000 (“about half” of which came from a government grant, he said) maintaining it, and now rents it out as a guesthouse. It’s one of about 40 derelict Japanese properties he has restored over the years, all the while preaching the importance of conservation and rural revitalization. “Many cultures have wooden architecture, but when it comes to the techniques of carpentry, Japan overwhelmingly leads the world in joinery and use of materials, as well as use of space achoreography,” said Mr. Kerr. “When it comes to these old houses, you have all that, set in a natural environment, and within the context of being cheap.”

Mr. Kerr is the first to admit that akiya can be money pits. He has spent decades and roughly $700,000 (“about half” of which came from a government grant, he said) maintaining it, and now rents it out as a guesthouse. It’s one of about 40 derelict Japanese properties he has restored over the years, all the while preaching the importance of conservation and rural revitalization. “Many cultures have wooden architecture, but when it comes to the techniques of carpentry, Japan overwhelmingly leads the world in joinery and use of materials, as well as use of space achoreography,” said Mr. Kerr. “When it comes to these old houses, you have all that, set in a natural environment, and within the context of being cheap.”You can read the original article at nytimes.com