How can we repair our living spaces after devastating climate related disasters if we continue the very architectural habits that led us to disaster? The answer may lie in bioregional systems for materials, a more localized approach to the way we build our homes and habitats.

Architecture 2030, a non-profit, non-partisan organization established to respond to climate emergency, has calculated that 42% of global carbon emissions originate from the built environment, a large portion derived from the production and transportation of building materials such as cement and timber.

As Los Angeles rebuilds after the recent fire, its builders are poised to turn again to the conventional products: epoxied wood, plastic paints, and resin- or fiberglass-infused drywall. These materials are infused with petrochemicals and flowing from global sites of extraction into our homes. Smooth-coated and painted, finished and domesticated, their toxicity sits in slumber until the next fire.

As Los Angeles rebuilds after the recent fire, its builders are poised to turn again to the conventional products: epoxied wood, plastic paints, and resin- or fiberglass-infused drywall. These materials are infused with petrochemicals and flowing from global sites of extraction into our homes. Smooth-coated and painted, finished and domesticated, their toxicity sits in slumber until the next fire.

Bioregionalism, which posits a starkly different approach, has a long history in California, first emerging from the idealism of 1960s counterculture. Bioregions are areas of land or sea defined by a relationship to place—exceeding political or administrative systems, and potentially delimited by ecological and natural features. Desert plains, arroyo foothills, brackish watersheds, quick-moving rivers, mountain ranges and drainage basins are examples of bioregions.

As a concept, practice, and cultural technique, bioregioning encompasses no single definition—it can be defined by hard boundaries, like elevation shifts or riparian edges, or soft boundaries like biotic shifts, or spiritual places. “Bioregions themselves rest at the border between geography and history,” notes historian William G. Robbins.

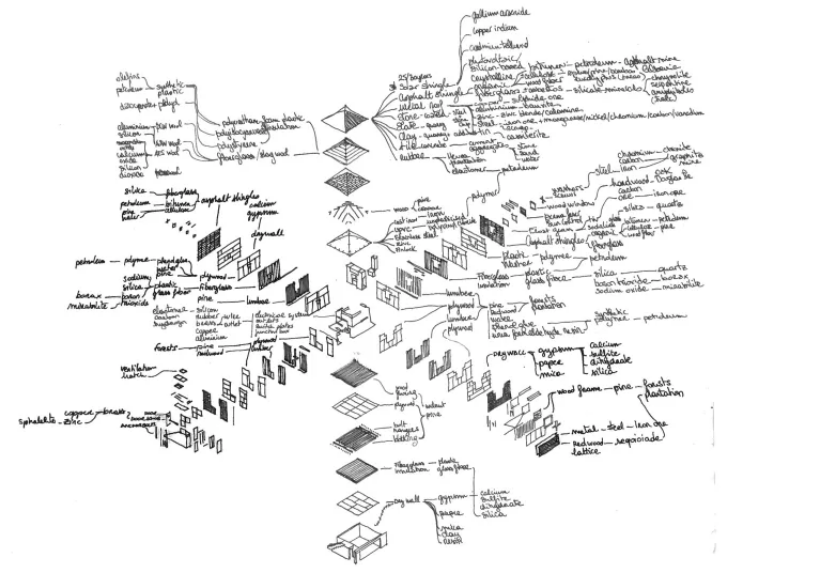

In architecture, bioregioning seeks building materials regionally, with renewal in mind. This may mean embracing indigenous and other long-standing, place-based construction systems, such as adobe building, or developing new materials sourced from local byproducts, such as algae-based bricks. The bioregional ethos advocates for systemic shifts in building economies through de-scaling or circularity—creating regenerative systems to manage its residue and avoid exporting its waste.

The strategy report “Islands of Coherence,” by the U.K.-based Future Observatory Journal, explores the systemic shifts required to transform political governance and civil society around local ecosystems, material flows, and regeneration. All construction components can be drawn from nearby and derive from materials such as agricultural products (sunflowers, straw, rice), and industrial waste (bricks, tiles, etc.) “Materials are heavy and should stay local,” the lab notes. “Ideas and people are light and are global.”

Some are rediscovering adobe, which is both fire-resistant and locally produced. Often sourced from the building site itself, soil utilized in adobe construction offers a circular system where a site’s soil constructs a building and then returns to earth. Education and advocacy organizations, such as Adobeisnotsoftware and SuperAdobe research center CalEarth, are activating a bioregional network of material practitioners interested in earthen construction.

Bioregioning advocates want to turn waste byproducts into building components, too. Some 30 to 40% of domestic landfill waste comes from building demolition. The design-build firm CarbonShack has built a home in L.A.’s Mount Washington by redirecting the byproducts of dismantled buildings in the surrounding area into renewed housing. Sourcing from building byproducts and demolition waste extends the lives of nonrenewable resources.

There is currently no university, municipal, or county-funded policy or program committed to supporting bioregional material inventories and building systems. In the aftermath of the Los Angeles wildfires, a chorus of opinions rose and fell in the ashy wake of the devastation—yet a coherent, sustained strategy, network, and organization for rebuilding is still missing. Solutions remain individual, rather than collective. By centering non-extractive bioregional systems and approaches, we can cultivate a reparative architecture rather than merely a defensive one.

You can read the original article at www.zocalopublicsquare.org