Architect and designer Jenna Yu’s home in Providence, Rhode Island features wooden siding on an addition connected to the original 19th-century home. The addition was built with panelized straw.

Architect and designer Jenna Yu’s home in Providence, Rhode Island features wooden siding on an addition connected to the original 19th-century home. The addition was built with panelized straw.

The walls were plastered by her family and friends with earthen plaster, and the light fixtures were handcrafted by her mother and step-father. With two young children, Yu says that she was especially focused on creating a space that would be safe for her kids — lead-free and nontoxic. In addition to using biomaterials, Yu strived to incorporate elements of passive building, a high standard of energy efficiency for built structures, in her design.

The walls were plastered by her family and friends with earthen plaster, and the light fixtures were handcrafted by her mother and step-father. With two young children, Yu says that she was especially focused on creating a space that would be safe for her kids — lead-free and nontoxic. In addition to using biomaterials, Yu strived to incorporate elements of passive building, a high standard of energy efficiency for built structures, in her design.

Yu studied architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design and then returned to her home state of California, where she worked in straw bale construction, holding straw bale workshops with the California Straw Building Association for several years. When she returned to Rhode Island, she wanted to bring the design practice with her.

Yu studied architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design and then returned to her home state of California, where she worked in straw bale construction, holding straw bale workshops with the California Straw Building Association for several years. When she returned to Rhode Island, she wanted to bring the design practice with her.

“I had been doing straw bale construction for a few years. People will frame the whole building, and then they’ll get rough straw bales and have to use chainsaws to cut them around the wood,” she said. “And then you have to plaster it.” But in Providence, she opted to use panelized straw, a choice she said is gaining traction among those in straw bale construction. Yu explained that the entire addition — panels and all — arrived in one shipping container from Lithuania. From breaking ground to clearing away construction materials, the project took just over a year to complete.

“I had been doing straw bale construction for a few years. People will frame the whole building, and then they’ll get rough straw bales and have to use chainsaws to cut them around the wood,” she said. “And then you have to plaster it.” But in Providence, she opted to use panelized straw, a choice she said is gaining traction among those in straw bale construction. Yu explained that the entire addition — panels and all — arrived in one shipping container from Lithuania. From breaking ground to clearing away construction materials, the project took just over a year to complete.

With Providence’s accessory dwelling unit (ADU) laws in flux, she had to adjust her plans for a standalone structure. The zoning regulations at the time instead required the structure be attached to her existing house — essentially creating a duplex.

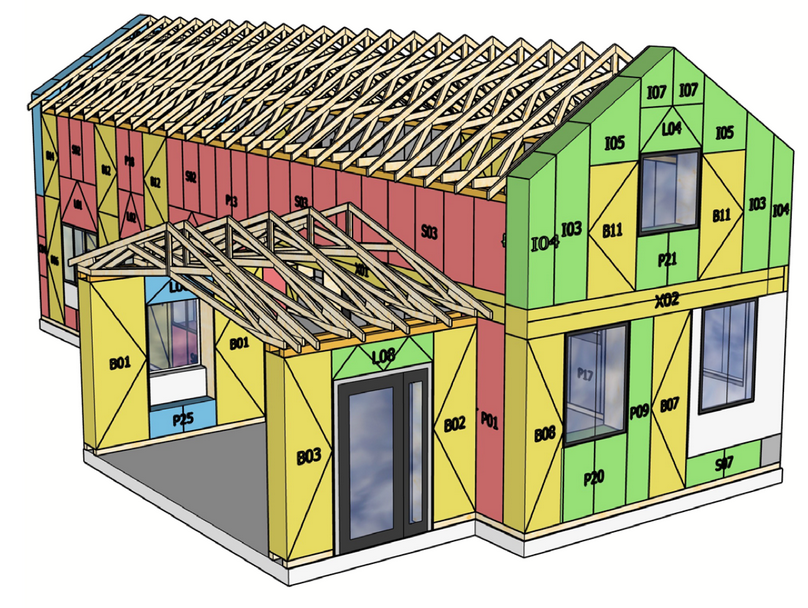

Once permitting was good to go, they broke ground, creating a massive pit. These panels are comprised of pressed straw, enclosed in wood. Diagonal bracing is used to ensure structural integrity. She used EcoCocon, a Lithuanian company, to source the straw panels. Yu wrote about the process and floor plans for the addition in-depth for The Last Straw in an article titled Straw Panel Prototype.

Once permitting was good to go, they broke ground, creating a massive pit. These panels are comprised of pressed straw, enclosed in wood. Diagonal bracing is used to ensure structural integrity. She used EcoCocon, a Lithuanian company, to source the straw panels. Yu wrote about the process and floor plans for the addition in-depth for The Last Straw in an article titled Straw Panel Prototype.

EcoCocon helps with the assembly process by creating a 3D model of where each panel should be installed. The panels were lifted into place using a forklift, and the trusses were attached. The house was weather-tight within five days. The walls also naturally serve as carbon storage, which Yu said is essential.

EcoCocon helps with the assembly process by creating a 3D model of where each panel should be installed. The panels were lifted into place using a forklift, and the trusses were attached. The house was weather-tight within five days. The walls also naturally serve as carbon storage, which Yu said is essential.

The house is designed to be comfortable without relying on mechanical systems, using natural ventilation and thermal mass.

The house is designed to be comfortable without relying on mechanical systems, using natural ventilation and thermal mass.

The house has a “truth window” — a design choice common in straw bale homes — revealing the material behind the plaster.

The house has a “truth window” — a design choice common in straw bale homes — revealing the material behind the plaster.

Though some may be skeptical about the efficacy of natural building materials in a place like Providence, Yu’s own home shows that it can be done — and can serve as a homey, inviting place while also helping to sequester carbon.

Though some may be skeptical about the efficacy of natural building materials in a place like Providence, Yu’s own home shows that it can be done — and can serve as a homey, inviting place while also helping to sequester carbon.

She mentioned that EcoCocon may look to open a U.S.-based factory, which would make the process easier. Yu explained that the current options in the United States are costlier and take longer.

You can read the original article at ecori.org

More North American cities should get rid of strict single-family zoning and embrace missing middle dwelling units such as duplexes, semi-detached houses, short rows of rowhouses, small 3-12 unit apartment houses, tiny home pocket neighborhoods, etc. Moreover, they should also embrace alternative construction methods and materials. This would help solve the housing crisis. After all, the average home price or rent is too prohibitively expensive for most younger people to afford their own homes.