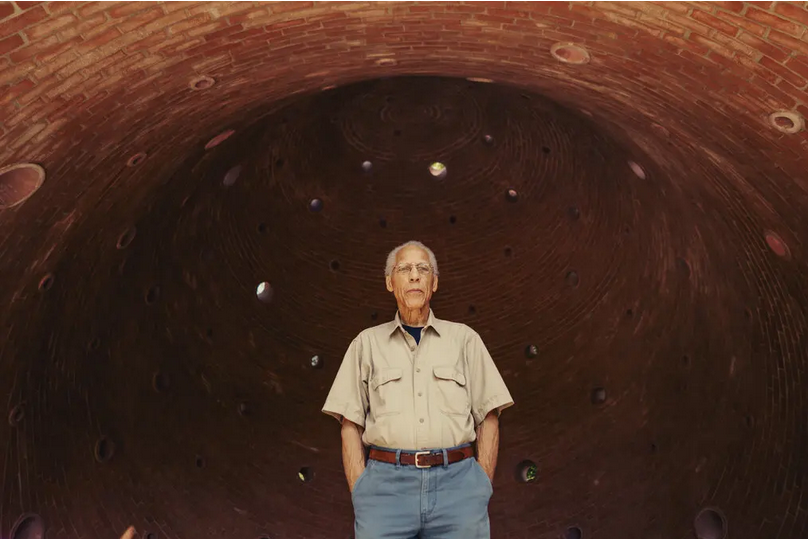

“Lookout,” located on a hilltop in a wooded corner of the Storm King Art Center, is sculptor Martin Puryearthe’s latest work.

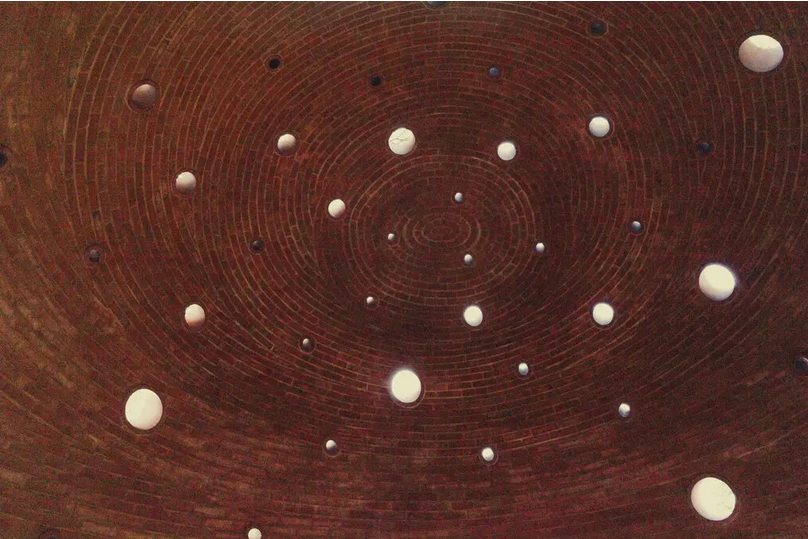

“Lookout,” which has 90 openings of varying dimensions, is his first piece in brick. He claims that this is his most complicated sculpture to date. It uses a technique known as Nubian vaulting, developed thousands of years ago in the Upper Nile delta. Bricks can be laid at angles rather than just horizontally and the technique requires a fast-setting mortar. “You can create a span without having formwork,” Martin explains. “The bricks are supported by the previous course of bricks.”

“Lookout,” which has 90 openings of varying dimensions, is his first piece in brick. He claims that this is his most complicated sculpture to date. It uses a technique known as Nubian vaulting, developed thousands of years ago in the Upper Nile delta. Bricks can be laid at angles rather than just horizontally and the technique requires a fast-setting mortar. “You can create a span without having formwork,” Martin explains. “The bricks are supported by the previous course of bricks.”

“I love that it comes from Africa,” he said of the technique’s origins. In the 1960s, he worked in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone for two years, during which he learned local craft traditions from potters, weavers and woodcarvers. His stay there left a profound impression on him. “It was a moment when I was able to have firsthand experience of a part of the continent that produced the African American population,” Puryear said. “The nature of the trade of people from Africa, that rupture, makes it difficult for Black people to connect back to the continent. We have to look through that veil to understand our origins,” he added. “It’s a cruel irony.”

It was a 2009 visit to another African country, Mali, that had a direct effect on “Lookout.” “I saw a roof being made in a village, and it had no internal formwork — that was a significant moment to unlock the structural principle of this piece,” he said of the vaulting technique in “Lookout.”

Now 82 years old, Martin’s art production spans more than a 50-year career. Some of his career highlights included public works like the 40-foot-tall Madison Square Park installation “Big Bling” (2016), and his representation of the United States at the 2019 Venice Biennale with “Liberty.”

Now 82 years old, Martin’s art production spans more than a 50-year career. Some of his career highlights included public works like the 40-foot-tall Madison Square Park installation “Big Bling” (2016), and his representation of the United States at the 2019 Venice Biennale with “Liberty.”

The new work is made of two layers of brick sandwiched around concrete-reinforced stainless rebar. “It’s built to stand the test of time,” he says. It can be entered under a brick archway on one side, and then it rises toward a dome. “It’s like being in a grotto,” he said, or a “brick pouch.” There is something chapel-like about the interior too, and that tracks with his previous works that reflect his Catholic upbringing.

The new work is made of two layers of brick sandwiched around concrete-reinforced stainless rebar. “It’s built to stand the test of time,” he says. It can be entered under a brick archway on one side, and then it rises toward a dome. “It’s like being in a grotto,” he said, or a “brick pouch.” There is something chapel-like about the interior too, and that tracks with his previous works that reflect his Catholic upbringing.

The 90 openings are all aligned on a center spot that was temporarily occupied by a pole topped with a tennis ball, standing in for a viewer. “The real point about the holes is that they all point to one spot,” he said. “When you reach it, you’ll be able to look out equally well through all of them.”

For the artist, “Lookout” is most engaging as an exercise in pure form. “It’s about the transition between the tunnel and the dome, and how to realize that,” he said. “That was the challenge.” This work “feels like a breath of fresh air.”

For the artist, “Lookout” is most engaging as an exercise in pure form. “It’s about the transition between the tunnel and the dome, and how to realize that,” he said. “That was the challenge.” This work “feels like a breath of fresh air.”

His goal with “Lookout,” he added, was “to make something for its own sake. I’m embracing the pure possibilities of delight and pleasure, of making and experiencing form and shape and light — all the things that art gives humanity.”

His goal with “Lookout,” he added, was “to make something for its own sake. I’m embracing the pure possibilities of delight and pleasure, of making and experiencing form and shape and light — all the things that art gives humanity.”

You can read the original article at www.nytimes.com

Resembles a potato