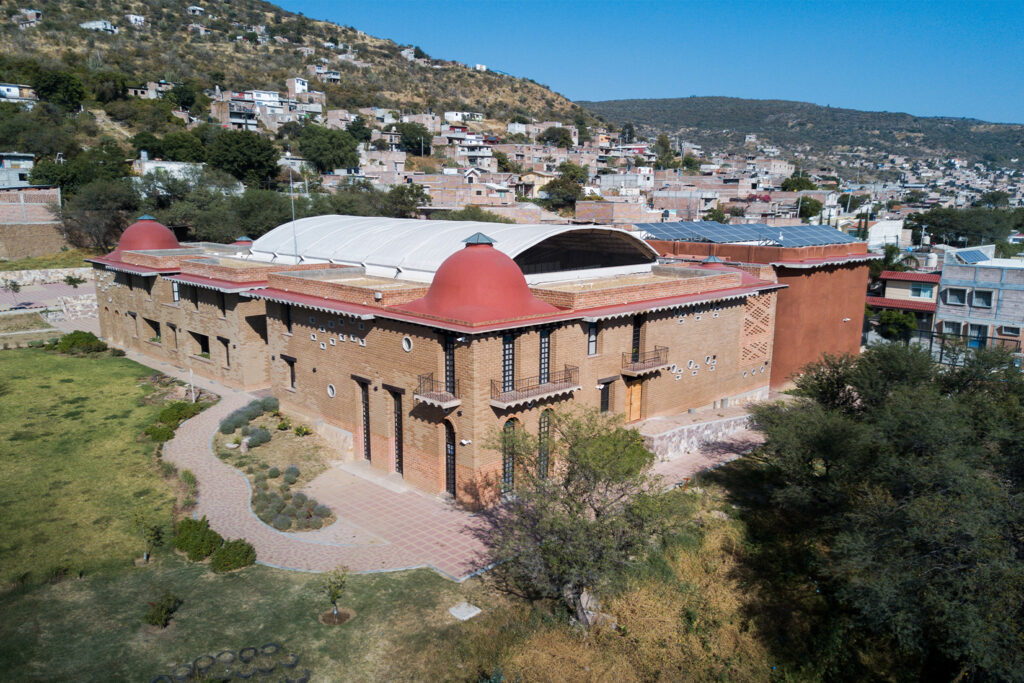

The Imagina cultural center on the outskirts of León, Mexico, is housed in a big, multistory facility, constructed mostly from locally dug adobe soil; it is engineered using bioconstruction techniques, a holistic building technique that aims to achieve a circular economy, minimizing waste and benefiting people. In fact, all 3,500 square meters (about 37,700 square feet) are meant to serve as a bold demonstration of bioconstruction principles.

Its two red domes reach gracefully skyward, and its roof is partly covered in solar panels. It’s a feel-good space inside, with excellent ventilation and pleasant temperatures maintained without air conditioning year-round. The center is flanked by a kitchen garden, flower garden, and an edible forest. The building also boasts composting toilets.

Its two red domes reach gracefully skyward, and its roof is partly covered in solar panels. It’s a feel-good space inside, with excellent ventilation and pleasant temperatures maintained without air conditioning year-round. The center is flanked by a kitchen garden, flower garden, and an edible forest. The building also boasts composting toilets.

“Harmony is the key principle,” says Peter van Lengen, Imagina’s lead architect. “Buildings need to be in harmony with the surrounding nature and community.” This implies not only the use of local, eco-friendly materials, but also the recruiting and training of local craftspeople. After receiving a crash course in building with adobe, 130 newly trained bricklayers from the city were hired to complete the two-year construction project.

“Harmony is the key principle,” says Peter van Lengen, Imagina’s lead architect. “Buildings need to be in harmony with the surrounding nature and community.” This implies not only the use of local, eco-friendly materials, but also the recruiting and training of local craftspeople. After receiving a crash course in building with adobe, 130 newly trained bricklayers from the city were hired to complete the two-year construction project.

When the building of Imagina was completed in 2016, its inauguration was a huge social event, attended by the state governor, city mayor, and also those who built it, including a proud group of young former substance abusers. “They were weeping when they were handed over a diploma for their participation,” Laura Alba, who works with Imagina, recalls. “Thanks to the diploma, many of them have found work elsewhere.”

When the building of Imagina was completed in 2016, its inauguration was a huge social event, attended by the state governor, city mayor, and also those who built it, including a proud group of young former substance abusers. “They were weeping when they were handed over a diploma for their participation,” Laura Alba, who works with Imagina, recalls. “Thanks to the diploma, many of them have found work elsewhere.”

Peter van Lengen is the son of Johan van Lengen, whose Barefoot Architect’s Manual became famous in the 1980s. It’s a tome nowadays recognized as the bioconstruction bible. Imagina’s completion was a dream come true for van Lengen too. “I thought it would be the beginning of a new era of bioconstruction,“ he says, because the 2016 grand opening nearly coincided with a crucial moment in international diplomacy, coming less than a year after the historic Paris climate agreement was reached.

Peter van Lengen is the son of Johan van Lengen, whose Barefoot Architect’s Manual became famous in the 1980s. It’s a tome nowadays recognized as the bioconstruction bible. Imagina’s completion was a dream come true for van Lengen too. “I thought it would be the beginning of a new era of bioconstruction,“ he says, because the 2016 grand opening nearly coincided with a crucial moment in international diplomacy, coming less than a year after the historic Paris climate agreement was reached.

Alejandra Caballero, a gray-haired woman who always wears overalls, is the director of Mexico‘s most famous bioconstruction school, the Proyecto San Isidro, situated on the outskirts of the of Tlaxco, a short drive from Mexico City. Her school consists of half a dozen adobe buildings — dormitories with bathrooms, a kitchen, and a green-roofed library — each with a unique design, using and displaying different bioconstruction methods.

Alejandra Caballero, a gray-haired woman who always wears overalls, is the director of Mexico‘s most famous bioconstruction school, the Proyecto San Isidro, situated on the outskirts of the of Tlaxco, a short drive from Mexico City. Her school consists of half a dozen adobe buildings — dormitories with bathrooms, a kitchen, and a green-roofed library — each with a unique design, using and displaying different bioconstruction methods.

When building a bathroom with adobe it must be made water-resistant. That requires a 2,000-year-old plastering technique called Moroccan stucco, which requires the mixing of adobe with lime in precise proportions, and then polishing with agate or obsidian stones. The result is a smooth, marbled, water-repellent surface.

Bioconstruction requires hands-on skill, not heavy machinery, so it creates lots of jobs and therefore a healthier, more resilient local economy. It can also lower the long-term costs of heating and air conditioning, in some environments reducing them to zero.

Bioconstruction requires hands-on skill, not heavy machinery, so it creates lots of jobs and therefore a healthier, more resilient local economy. It can also lower the long-term costs of heating and air conditioning, in some environments reducing them to zero.

Bioconstruction can also last for centuries. To illustrate that point, one need look no further than Arg-e Bam in Iran, a trading center on the famous Silk Road. Bam was built in the third century entirely of mud clay bricks and the trunks of palm trees. In German cities, one can still find beautifully conserved timber clay construction from the Medieval period.

Bioconstruction can also last for centuries. To illustrate that point, one need look no further than Arg-e Bam in Iran, a trading center on the famous Silk Road. Bam was built in the third century entirely of mud clay bricks and the trunks of palm trees. In German cities, one can still find beautifully conserved timber clay construction from the Medieval period.

Bioconstruction also suffers from the realities and misperceptions of today’s conventional home building and real estate markets: When considering bioconstruction, “Owners are afraid of high maintenance costs, about not being able to resell the house, and credit or financing that is hard to obtain,” says van Lengen. But those fears arose relatively recently. Bioconstruction with adobe was very popular in Mexico until the revolution there in the 1920s. Yet, adobe Catholic missions, some enduring since the 16th and 17th centuries, still dot the Mexican and U.S. Southwest landscape today.

Bioconstruction also suffers from the realities and misperceptions of today’s conventional home building and real estate markets: When considering bioconstruction, “Owners are afraid of high maintenance costs, about not being able to resell the house, and credit or financing that is hard to obtain,” says van Lengen. But those fears arose relatively recently. Bioconstruction with adobe was very popular in Mexico until the revolution there in the 1920s. Yet, adobe Catholic missions, some enduring since the 16th and 17th centuries, still dot the Mexican and U.S. Southwest landscape today.

You can read the original article at news.mongabay.com

Pretty cool buildings for sure! Building with these organic, alternate materials is one of the few things that developing countries do better than developed nations, we can learn something from those “third world” countries. Mortgages, insurance and laws in most of the developed world (especially North America and Western Europe) aren’t very conducive to such construction practices unfortunately.