Some birds’ nests are cup-shaped, some have domes, others have been likened to apartment complexes. How do birds build their nurseries?

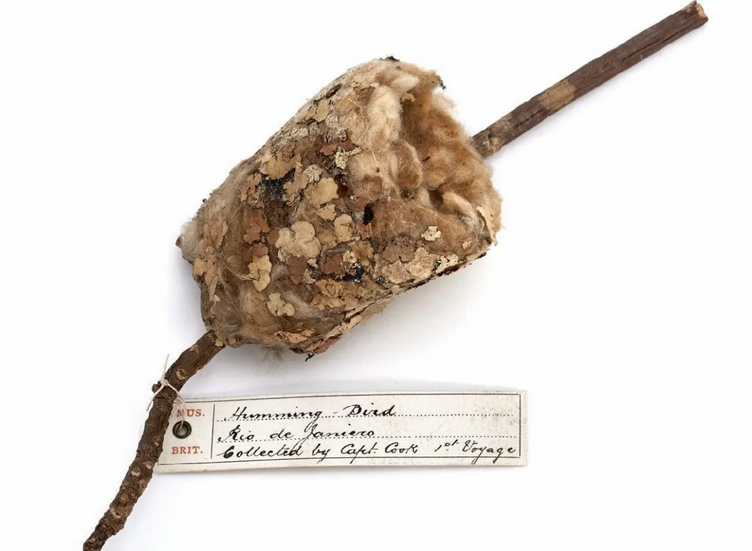

Captain Cook collected a hummingbird nest during his trip to Brazil. That nest, just 6 cm (2.4 inches) high was in the fork of two branches, camouflaged with lichen, lined with fluffy seeds and woven with cobwebs. Today, it is in London’s Natural History Museum, the oldest piece in a collection of more than 5000 bird nests. “That nest is a small encapsulation of the environment of Rio de Janeiro in 1768,” says Douglas Russell, the museum’s curator of nests and eggs. The cup-shaped structure is a feat of engineering that has held together for 250 years. “We see this as avian architecture,” says Russell.

Captain Cook collected a hummingbird nest during his trip to Brazil. That nest, just 6 cm (2.4 inches) high was in the fork of two branches, camouflaged with lichen, lined with fluffy seeds and woven with cobwebs. Today, it is in London’s Natural History Museum, the oldest piece in a collection of more than 5000 bird nests. “That nest is a small encapsulation of the environment of Rio de Janeiro in 1768,” says Douglas Russell, the museum’s curator of nests and eggs. The cup-shaped structure is a feat of engineering that has held together for 250 years. “We see this as avian architecture,” says Russell.

There are about 10,000 bird species worldwide and possibly as many nest variations. Yet despite this abundance, scientists are still untangling how birds build their nurseries. Some are open cups, some have roofs and hang in a teardrop shape from branches, others seem like twiggy piles. They can be found on the ground, in waterside grasslands, on cliff sides or in the nooks and crannies of buildings.

There are about 10,000 bird species worldwide and possibly as many nest variations. Yet despite this abundance, scientists are still untangling how birds build their nurseries. Some are open cups, some have roofs and hang in a teardrop shape from branches, others seem like twiggy piles. They can be found on the ground, in waterside grasslands, on cliff sides or in the nooks and crannies of buildings.

Scientists believe that bird nests probably started as just a scrape on the ground. Pigeons are legendary for making flimsy, apparently slapdash constructions with just a few twigs. But most birds make more complex and protective nests.

The bee hummingbird makes the smallest nest, about the size of a thimble. They lay two eggs smaller than the size of garden peas. Among the biggest nests are those of the wedge-tailed eagle, which erects a raft-like platform spanning several meters and weighing up to 400 kilograms.

The bee hummingbird makes the smallest nest, about the size of a thimble. They lay two eggs smaller than the size of garden peas. Among the biggest nests are those of the wedge-tailed eagle, which erects a raft-like platform spanning several meters and weighing up to 400 kilograms.

What we think of as the typical nest is a cup-shaped basket, often with rigid sticks for the outside walls, fluffy seed material as a layer of insulation and softer grasses or twigs to pad the interior. Birds build deeper cup shapes in locations with higher wind speeds to block the chill and thinner walls to ensure drainage in places prone to rainfall.

One of the most noticeable differences in nest architecture is the presence, or not, of a roof. Nests with roofs, also called domed nests, typically hang from trees, usually with an entrance on the side or a tunnel dangling below. The enclosed structure is widely thought to prevent predation from snakes, cats, foxes, rats and even other birds. South Africa’s Cape Penduline tit builds a pear-shaped felt enclosure that hangs from a branch like a bag. From the outside, a cavity appears to be the entrance, but the actual door is a few centimeters above and can be stuck down.

One of the most noticeable differences in nest architecture is the presence, or not, of a roof. Nests with roofs, also called domed nests, typically hang from trees, usually with an entrance on the side or a tunnel dangling below. The enclosed structure is widely thought to prevent predation from snakes, cats, foxes, rats and even other birds. South Africa’s Cape Penduline tit builds a pear-shaped felt enclosure that hangs from a branch like a bag. From the outside, a cavity appears to be the entrance, but the actual door is a few centimeters above and can be stuck down.

Enclosed nests are common in Australia: fairy-wrens, thornbills and lyrebirds all make them. Roofs are mostly to do with climate. “Exposure to the sun, once the parents leave the nest, could raise the temperature of the eggs, and they could die.”

Some birds nest in colonies. The Village Weaver has up to 150 neighbors, each in a nest hanging from the same cluster of trees. The Sociable Weaver, on the other hand, builds a kind of apartment complex in a tree: vast interconnected nests that look like haystacks, housing up to 300 birds. In Australia, cliff swallows build in smaller colonies of a dozen or so. The nests are made from mud and, with their rounded entries, appear like small pots or tubes of coral.

Rather than build from scratch, some birds use existing cavities. Many species of kingfishers repurpose termite mounds. The termites, realizing the bird isn’t a predator, will seal off the compartment once the bird settles in to nest.

Bird nests have inspired human designs, too. Crow’s nests have been a feature on sailing ships since ancient times.

The designs of birds’ nests are clever and often complex. Birds generally build in spring, when lengthening daylight hours signal a surge in plant growth with building materials. The nest site is chosen carefully, down to finding a suitable branch. In Australia, a Yellow Robin will look for a perfect vertical V; the Willie Wagtail builds only on flat forks; some Honeyeaters seek out leafy twigs to dangle their nest from, like an open purse.

The designs of birds’ nests are clever and often complex. Birds generally build in spring, when lengthening daylight hours signal a surge in plant growth with building materials. The nest site is chosen carefully, down to finding a suitable branch. In Australia, a Yellow Robin will look for a perfect vertical V; the Willie Wagtail builds only on flat forks; some Honeyeaters seek out leafy twigs to dangle their nest from, like an open purse.

Different species have distinctive techniques: sticking together, molding, piling up, interlocking, sewing and weaving. The purpose of all these techniques is to ensure that the nest stays attached to the nest site and that the components do not fall apart. Some species fly through spider webs that adhere to their beaks; some use their own saliva.

Some birds mix mud through the sticks, bark and straw they form the nest with. The bird molds the mud into shape before it hardens like plaster and sticks the nest to the branch. Swallows can be seen shaking their heads after gathering a mouthful of mud to mix the saliva with it.

Some of the trips the birds make from the nest are to discard material they have collected, a sign they refine the pile as they build. Blue Tits weave as they go putting parts all the way through; a bit like putting your wall beams up and putting the insulation in before you do anything else.”

The male African Southern Masked Weaver first cleans a branch of moss or loose bark, and ties several pieces of grass from it so they dangle as strands. Then he hangs upside down and ties those stands into a ring, using his foot to hold strands in place as he ties knots. This forms a frame to which he returns with more grass, which he begins to weave into the frame.

The male African Southern Masked Weaver first cleans a branch of moss or loose bark, and ties several pieces of grass from it so they dangle as strands. Then he hangs upside down and ties those stands into a ring, using his foot to hold strands in place as he ties knots. This forms a frame to which he returns with more grass, which he begins to weave into the frame.

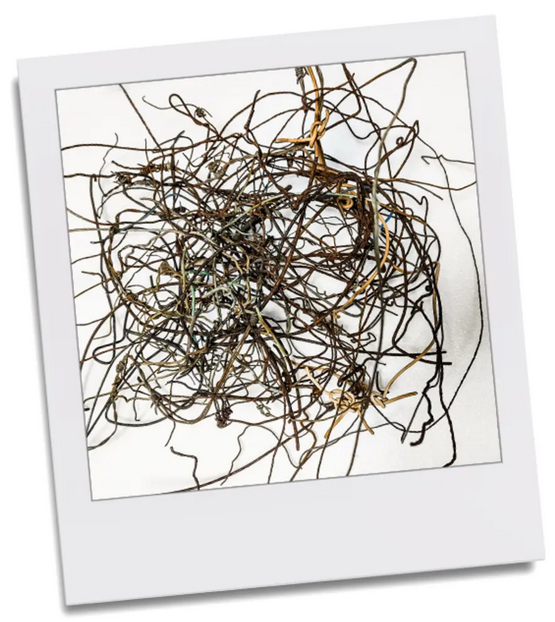

One magpie nest had metal and wire, plastic coat hangers, electrical wires, chicken wire, 3D glasses, metal springs, a phone charger, a Champagne cork, dental floss, headphones, baling twine and a saw blade.

One magpie nest had metal and wire, plastic coat hangers, electrical wires, chicken wire, 3D glasses, metal springs, a phone charger, a Champagne cork, dental floss, headphones, baling twine and a saw blade.

You can read the original article at www.smh.com.au

Birds don’t need government permission to build either. We’re the only species that has to ask permission to live on our own planet.

Doesn’t seem fair does it?

It’s almost as if ancient cultures used bird nests as the basises of their wigwams and other shelters