Barns provide a multi-purpose system of storage built to accommodate living things. Barns are houses for activities that involve humans, but are not built exclusively for them.

Barns are storehouses that operate as supply infrastructure for crops. The annual cycle of grain crop production often entails specific rituals or agricultural rites— procedures that entangle human society with natural cycles and the biome—that enable its reproduction.

Barns are storehouses that operate as supply infrastructure for crops. The annual cycle of grain crop production often entails specific rituals or agricultural rites— procedures that entangle human society with natural cycles and the biome—that enable its reproduction.

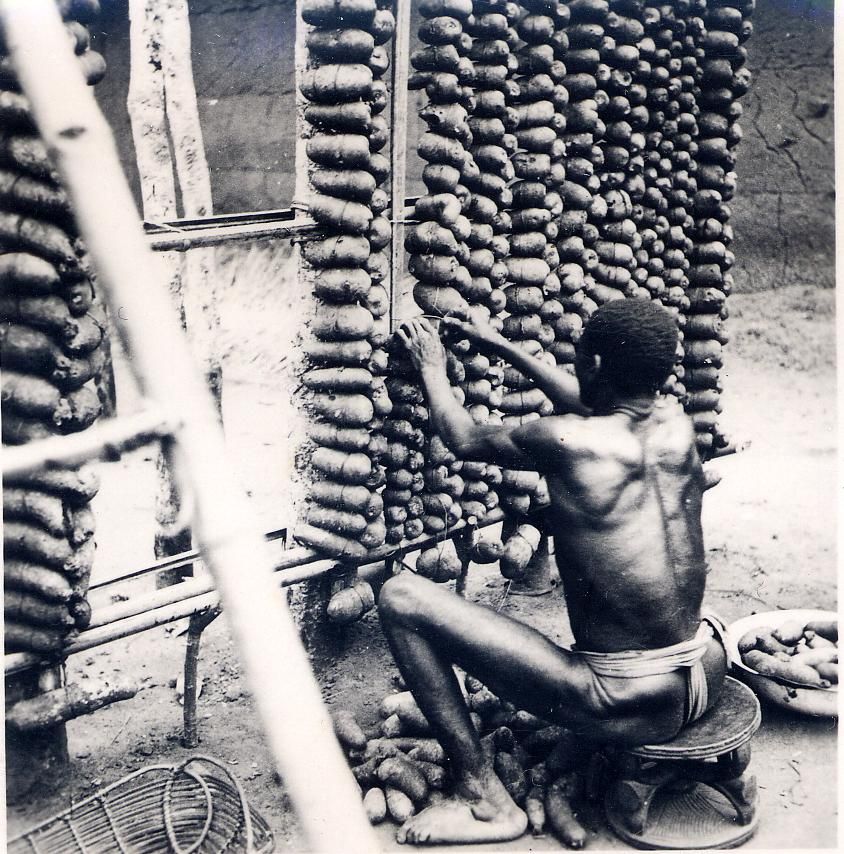

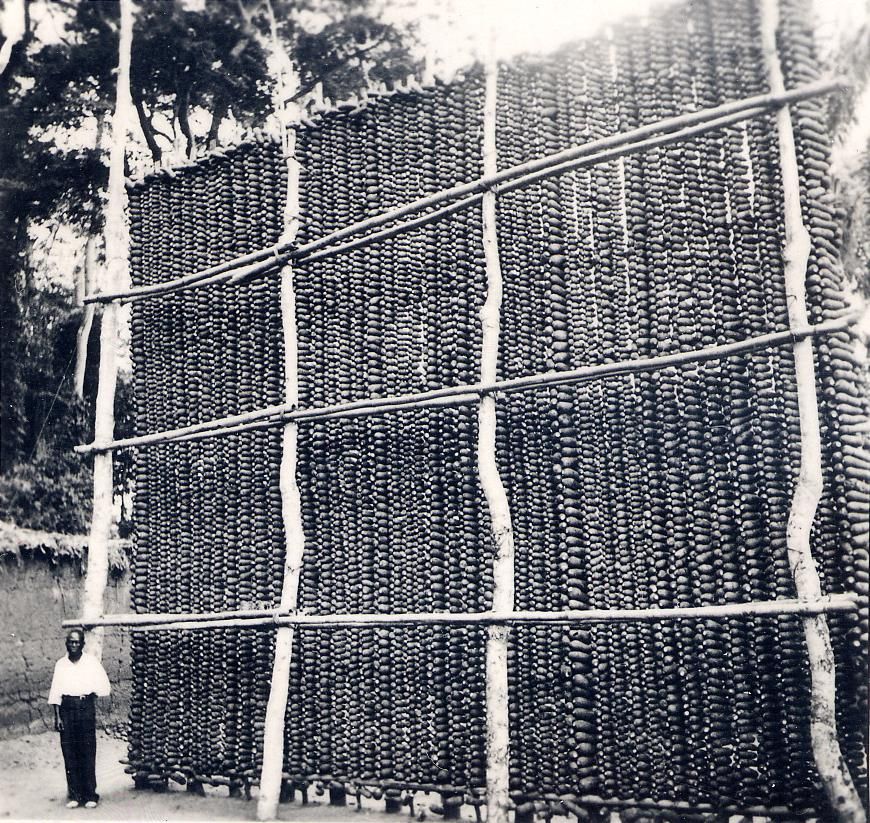

Where grains are seeds that can yield new cereal crops, yams grow from seed yams: tubers that propagate new yams that are close to the original cultivar lineage. Among the Igbo people of present-day Nigeria and neighboring countries, there is a strong relationship between the health of the land for yam cultivation, nobility, rank, and wealth. When the yam crop is first harvested, the tubers must be cured for a period of days up to several weeks. After curing, they are traditionally tied with natural fiber twine or rope around their equator in vertical chains to wooden stick frames. This keeps them away from vermin and dampness at ground-level; facilitates regular inspection of individual tubers to remove any overripe, infected, or otherwise undesirable ones; and visually demonstrates a family’s bio-material wealth—an insurance policy for survival from one season to the next.

Where grains are seeds that can yield new cereal crops, yams grow from seed yams: tubers that propagate new yams that are close to the original cultivar lineage. Among the Igbo people of present-day Nigeria and neighboring countries, there is a strong relationship between the health of the land for yam cultivation, nobility, rank, and wealth. When the yam crop is first harvested, the tubers must be cured for a period of days up to several weeks. After curing, they are traditionally tied with natural fiber twine or rope around their equator in vertical chains to wooden stick frames. This keeps them away from vermin and dampness at ground-level; facilitates regular inspection of individual tubers to remove any overripe, infected, or otherwise undesirable ones; and visually demonstrates a family’s bio-material wealth—an insurance policy for survival from one season to the next.

Traditional yam barns tend to be less enclosed than their grain barn counterparts. Typically located within a broader agricultural terrain situated in between the home or domestic space and the farm, they are erected as a loose network of “occupiable scaffolding,” consisting primarily of wooden stakes or bamboo poles used to support individual tubers.

Traditional yam barns tend to be less enclosed than their grain barn counterparts. Typically located within a broader agricultural terrain situated in between the home or domestic space and the farm, they are erected as a loose network of “occupiable scaffolding,” consisting primarily of wooden stakes or bamboo poles used to support individual tubers.

The Anam Development Company is on a site that includes an array of housing (ranging from compound housing around a central courtyard to vernacular wattle-and-daub construction and different housing prototypes), a compressed earth block factory, a borehole well for potable water, and earth ponds set among stands of trees, palms, bamboo, and abundant terrestrial and freshwater fauna. The surrounding landscape is a riverine area prone to seasonal flooding, which required the construction timeline to be organized in relation to the rainy season.

The Anam Development Company is on a site that includes an array of housing (ranging from compound housing around a central courtyard to vernacular wattle-and-daub construction and different housing prototypes), a compressed earth block factory, a borehole well for potable water, and earth ponds set among stands of trees, palms, bamboo, and abundant terrestrial and freshwater fauna. The surrounding landscape is a riverine area prone to seasonal flooding, which required the construction timeline to be organized in relation to the rainy season.

As a result, the design of the barn utilized a hybrid fast-build technique, using light steel columns to prop up a roof while walls were under construction. This introduced additional strength and rigidity to the structure while allowing natural ventilation via a clerestory-level air gap between the eaves and breezeblock masonry walls. The inclusion of modest roof projections also created low-cost porch conditions capable of buffering the entrance from both the sun and rain while allowing for the entire edge of the building to function as an intermediate zone.

As a result, the design of the barn utilized a hybrid fast-build technique, using light steel columns to prop up a roof while walls were under construction. This introduced additional strength and rigidity to the structure while allowing natural ventilation via a clerestory-level air gap between the eaves and breezeblock masonry walls. The inclusion of modest roof projections also created low-cost porch conditions capable of buffering the entrance from both the sun and rain while allowing for the entire edge of the building to function as an intermediate zone.

At its core, architectural form corresponds to a network of metaphysical relationships: the invisible structure of eco-politics governing how human society and nature interact. Architecture is the apparatus through which we inhabit the Earth. As storehouses that provide a dynamic equilibrium of stability and flexibility to sustain life, barns offer lessons on the fundamental reciprocity of building. Architecture can become so preoccupied with housing people that it can ignore the houses we build for other lifeforms. Buildings that support the survival of animals and their offspring or plants to live across cycles of seed dormancy, cultivation, and harvest are architectures that themselves live. How we think about architecture, space, consciousness, ourselves, one another, nature, and the universe determines what we build.

At its core, architectural form corresponds to a network of metaphysical relationships: the invisible structure of eco-politics governing how human society and nature interact. Architecture is the apparatus through which we inhabit the Earth. As storehouses that provide a dynamic equilibrium of stability and flexibility to sustain life, barns offer lessons on the fundamental reciprocity of building. Architecture can become so preoccupied with housing people that it can ignore the houses we build for other lifeforms. Buildings that support the survival of animals and their offspring or plants to live across cycles of seed dormancy, cultivation, and harvest are architectures that themselves live. How we think about architecture, space, consciousness, ourselves, one another, nature, and the universe determines what we build.

You can read the original article at www.e-flux.com

You can read the original article at www.e-flux.com