The use of raw earth to build public and private structures has been practiced for thousands of years, with over 1.7 billion people across the globe living in earthen homes. But its integration in urban infrastructure and planning is something we ought to explore more.

Raw earth with other materials left to dry and harden under the sun has sustained the test of time. Walls built with cob are known to have good thermal mass and when that is combined with thatched straw roofs or terracotta tiles, it can make for a comfortable interior.

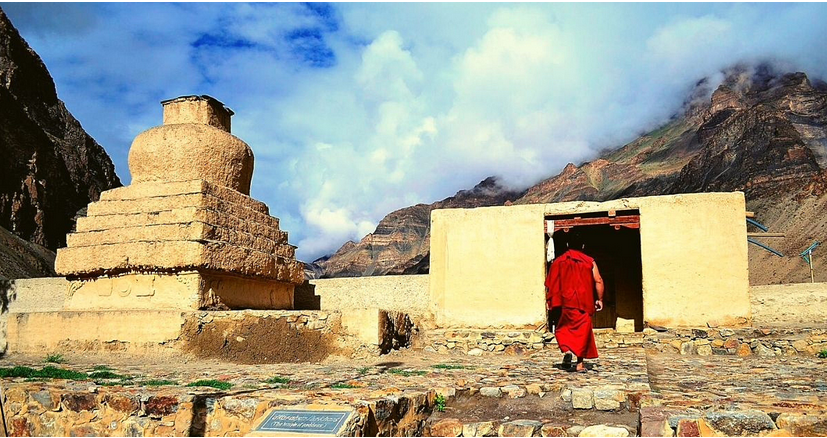

A living proof of this is the famous Tabo mud monastery in Spiti Valley, India. Built in 996 CE, by Tibetan Buddhists, this monastery is the oldest standing cob structure in India. Raw earth is predominantly used in the region, even to build the flat-roofed traditional houses.

A living proof of this is the famous Tabo mud monastery in Spiti Valley, India. Built in 996 CE, by Tibetan Buddhists, this monastery is the oldest standing cob structure in India. Raw earth is predominantly used in the region, even to build the flat-roofed traditional houses.

Steeped in mythology and spirituality, these walls bear centuries worth of strength, allowing them to withstand the extreme Himalayan weather, especially during the winters and earthquakes. It was only in 1975, that the monastery’s structure, after having survived several natural disasters, eventually faced a major threat because of an earthquake. Although the earthquake managed to harm the structure, its superior building quality allowed it to stand until a reconstruction project was initiated in 1983 with the 14th Dalai Lama at the helm. Now protected by the Archaeological Survey of India as a national historic treasure, the monastery showcases the art adorning its interior.

The UN World Commission on Environment and Development encourages sustainable building solutions that meet the needs of the present without compromising on the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, especially in terms of usage of natural resources. It is time for innovative sustainable techniques that compliment ancient earthen structures like this while improving its overall strength and durability.

The UN World Commission on Environment and Development encourages sustainable building solutions that meet the needs of the present without compromising on the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, especially in terms of usage of natural resources. It is time for innovative sustainable techniques that compliment ancient earthen structures like this while improving its overall strength and durability.

You can read the original article at www.thebetterindia.com