In 2013, Jay Thakkar discovered a traditional wood and stone building with a slight tilt in the Kullu district of Himachal Pradesh. When he asked a local villager about it, he responded, “Sir, the house tilted when the earth moved. It will move back once the earth shifts again.” Thakkar, an associate professor at the faculty of design and co-founder, Design Innovation and Craft Resource Centre, at CEPT University, Ahmedabad, has been researching Himachal Pradesh’s kath khuni architecture and other indigenous building practices of the Himalaya since 2005.

Stories of the earth shifting are common in the Himalayan belt—from Kashmir to Assam—which has been witness to massive earthquakes over the past two centuries. The most recent of these, in 2005 in Kashmir, killed 86,000 on both sides of the border. This year, as Himachal Pradesh witnesses unprecedented rainfall and flash floods, it continues to suffer lethal landslides. More than 200 roads in the region are inaccessible.

But even as the earth continues to shift in the Himalaya, the stories of houses adjusting themselves to this have become few and far between. For the local wood-and-stone architecture has given way to pukka cement and RCC.

In the early 20th Century an indigenous style of architecture called kath kuni was prevalent, made with wood and stone in equal parts. During earthquakes, the channels didn’t budge. Even if the stones on one side of the structure shifted, the other side would fill them up.

In the early 20th Century an indigenous style of architecture called kath kuni was prevalent, made with wood and stone in equal parts. During earthquakes, the channels didn’t budge. Even if the stones on one side of the structure shifted, the other side would fill them up.

In recent years, there has been an effort to document and research traditional styles as some architects, designers and local builders look to the past to build anew while incorporating modern design and amenities to offer viable alternatives. Although state governments are yet to show much interest, an individual-led effort exists to document and research these styles.

Each disaster drives home the resilience of local architecture whose techniques evolved over centuries to withstand seismic tremors and small floods. Take, for instance, the dhajji dewari and taq styles in Kashmir, koti banal in Uttarakhand, Assam-style houses in Assam and kath khuni in mid and central Himalaya. Each of these was rooted in the local context, making use of material available in the vicinity and employing techniques that offered resilience against shifts of the earth.

The architecture in the western Himalaya, for instance, focused on wood and stone frameworks that didn’t use metal nails. It was economical, too, for the cost of rebuilding, in case of damage, was less than that of pukka houses. One could reuse the wood and stone to restore the original structure.

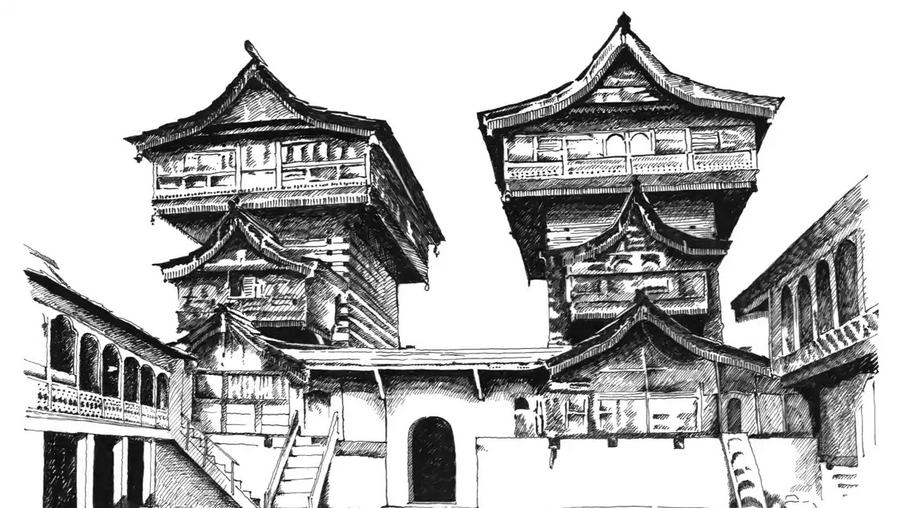

A kath khuni wall should have wood only on its corners or angles and stone as layers in between. The technique has proven incredibly durable, with some buildings standing for decades or centuries against various environmental forces. The locally sourced materials used in this technique, such as stone, wood and slate, possess unique characteristics that make them superior choices for construction when considering sustainability and performance. Kath khuni can be seen in granaries, temples, houses, even palaces.

A kath khuni wall should have wood only on its corners or angles and stone as layers in between. The technique has proven incredibly durable, with some buildings standing for decades or centuries against various environmental forces. The locally sourced materials used in this technique, such as stone, wood and slate, possess unique characteristics that make them superior choices for construction when considering sustainability and performance. Kath khuni can be seen in granaries, temples, houses, even palaces.

According to Thakkar, the carbon footprint of building a kath khuni house is lower than that of brick and mortar structures. “The wood would come from the surrounding forests. For temples, they obtained wood from dedicated sites where trees had grown for many years. As per the locals, there was a tradition of investing in the environment. The families sowed seeds when a child was born, and by the time they grew up, the trees were mature enough for use in construction. This was a way of giving back to the environment,” he explains.

The interesting aspect of this kind of construction lay in its dry masonry and the zero use of mortar. Since no metal nails are used, the structure relies on strategically inserted wooden braces and joints. “The stone is a compression material, while wood holds the building together. The higher the building goes, the more the use of wood and lesser the use of stone. The balconies spread out, providing a center of gravity to the building,” says Thakkar.

During an earthquake, the dry masonry holds its place and the cracks don’t travel up. In contrast, cement buildings, monolith structures, see cracks traveling up during tremors. “If stones from a kath khuni house fall out, they can be replaced without machinery or technology. The building relies on simple empirical knowledge,” says Thakkar.

In north-western Uttarakhand, the merits of koti banal, a quake-resistant form of architecture, too have been figuring in discussions among academics and disaster management experts for well over a decade. The significant components of koti banal: simple layout, construction on an elaborate, solid and raised platform, judicious use of locally available material such as wooden logs, stones and slate, incorporation of wooden beams all through the height of the building at regular intervals, small openings.

The massive solid platform at the base of the structure helps in keeping the center of gravity and center of mass in close proximity and near to the ground. This minimizes the overturning effect of the particularly tall structure during seismic loading.

The dhajji dewari style that used to be prevalent in Kashmir and parts of Himachal is like a quilted patchwork of stone and wood. Dhajji Dewari has been in practice for more than 200 years…. Dhajji Dewari emerged surprisingly earthquake resistant in the disastrous earthquake in Kashmir region in 2005.”

The move towards cement structures happened during the 1960s-70s, when the government invited cement industries to the state. Wood also became hard to come by. British-era forest laws had made it difficult for locals to access forests. Ever since the ban on taking wood from the forests without state permission, the black market for timber has started and resulted in wood prices soaring.

The masons, who specialized in stones, have moved to brick work to keep up with the demands of the times and rampant urbanization. The ones who worked with wood have moved on as well. They haven’t lost touch with the kath khuni style, though, as they are required to restore the doors or windows of temples from time to time.

You can read the original article at lifestyle.livemint.com