Witchcliffe Ecovillage in Western Australia will serve as home to around 700 people and be a model of sustainability for communities worldwide. The Ecovillage site spans about 300 acres of former farmland.  Project co-founders and partners, Mike Hulme and Michelle Sheridan began the project with a plan to create “the most sustainable residential community possible”. The entire development is to be carbon negative, sourcing its own energy, water and fresh food through solar and rainwater capture, regenerative agriculture practices, and passive solar and low carbon building techniques. Residents can design and build their own homes in accordance with the Ecovoillage’s fairly rigid sustainability guidelines, or purchase one of six pre-designed buildings.

Project co-founders and partners, Mike Hulme and Michelle Sheridan began the project with a plan to create “the most sustainable residential community possible”. The entire development is to be carbon negative, sourcing its own energy, water and fresh food through solar and rainwater capture, regenerative agriculture practices, and passive solar and low carbon building techniques. Residents can design and build their own homes in accordance with the Ecovoillage’s fairly rigid sustainability guidelines, or purchase one of six pre-designed buildings.

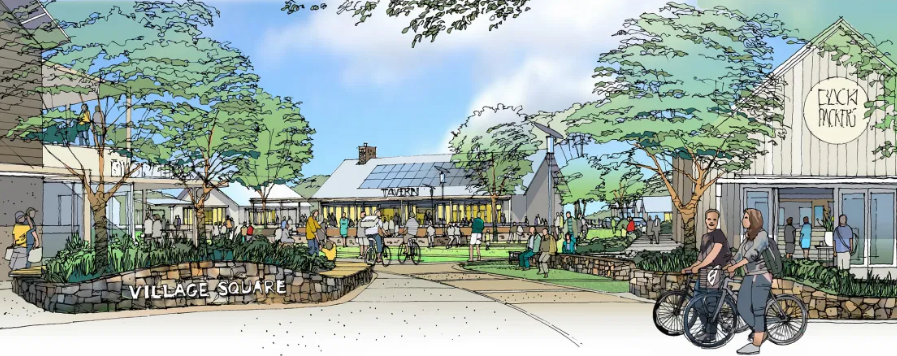

They expect to have a village square with Tavern, café, playground and co-working office spaces, as well as a commercial precinct and “food hub”. Witchcliffe will also feature a backpackers’ hotel and other tourism accommodation. “In time, we hope to attract visitors from all over the world who want to learn from what we’re doing and experience a holistic, sustainable community based on permaculture principles,” Hulme said.

It has taken over ten years for the Witchcliffe Ecovillage to achieve planning approvals and begin construction. Hulme said he was heartened by the overwhelming response and rate of interest which has driven the sale of over 100 lots so far, largely through word of mouth.

Jeff Thierfelder joined the project around two and a half years ago as project manager of architecture and planning, in time to see civil infrastructure completed for the initial stages of the development and residential construction commence. Personal interest drew Thierfelder and partner Jo to the project, and two decades of experience in architecture and town planning made him an ideal fit as it entered the crucial delivery stage. “We’re sort of coming in at the delivery end of it. The fun bit where you actually get to build the stuff,” Thierfelder said.

Jeff Thierfelder joined the project around two and a half years ago as project manager of architecture and planning, in time to see civil infrastructure completed for the initial stages of the development and residential construction commence. Personal interest drew Thierfelder and partner Jo to the project, and two decades of experience in architecture and town planning made him an ideal fit as it entered the crucial delivery stage. “We’re sort of coming in at the delivery end of it. The fun bit where you actually get to build the stuff,” Thierfelder said.

Step one of the construction process consisted of building two large dams that will serve as the source of irrigation for community gardens, agricultural lots, as well as storm water catchment and a place to cool off. An on-site sewage treatment plant will provide processed water to feed surrounding gardens.

Every household will have a rain catchment system to provide its own potable water, which is easily achievable when combined with dam water for landscaping and gardening. “The potable water supply is up to the individual. There’s a ratio about the roof size and the amount of water storage you need depending on how big your household is and we’re also specifying water efficient appliances as well as taps and shower heads as part of our design guidance,” Thierfelder said.

The development will be 100 per cent solar powered, with the aim of generating significantly more energy than it consumes and offsetting the carbon emissions created during the development process. Photovoltaic panels on every available roof top will feed into microgrids that enable power sharing between residents and businesses, which will be entirely electric.

A 232kW/hr Tesla Powerpack battery in every residential cluster will improve efficiency and feed electric vehicle charging stations for use by residents and visitors. The development is also connected to the main power grid with the intention of ultimately selling power back into the grid.

Houses are subject to life cycle and thermal assessments and are required to be carbon negative and use natural materials such as timber, stone, hempcrete, and straw bale.

“The objective we’ve got is that all of the houses are carbon negative enough so that at some point when it’s all finished hopefully that will account for all the hard infrastructure that’s gone into the land development, the roads and sewage system and so on.”

A major defining factor of the ecovillage is the intentional facilitating of communities and relationships between neighbors. Based on studies of group interactions and past experiences of communal living, the Ecovillage is broken up into clusters of typically between 20-25 lots and around 40-70 people. “It actually works better if you break it down into smaller increments so that there’s actually communities within communities,” Thierfelder said. “The way that those clusters will function will hopefully replicate some of the benefits that the cohousing movement has been able to achieve in terms of community formation.”

With little to speak of in terms of advertising, word of Witchcliffe Ecovillage has spread primarily to types of people most likely to be interested in a project of this type. Thierfelder said that other developers are watching closely to see if they might have missed a gap in the market that buyers are eager to see filled. “Hopefully now that I think we’re showing it’s commercially viable and successful, you’ll see some more developers doing similar types of projects. We’re pretty open source with our materials and if other developers want to try something similar we’re all for it,” Thierfelder said.

You can read the original article at thefifthestate.com.au