Iain Ruadh MacMaster arrived on Cape Breton Island from Scotland in 1801. He climbed the slope of his land grant—approximately 200 acres from the shoreline up and over the rise—and built his house on the hillside. Legend has it that a driving rainstorm washed that first house down the hill. So he set to building a small stone house, with walls two feet thick, a kitchen and a parlor below, and lofts for sleeping above. Iain named it Moidart, for the place he’d left behind. Here, in this new country, above the waves of St. Georges Bay, he and his wife raised 12 children.

Iain Ruadh MacMaster arrived on Cape Breton Island from Scotland in 1801. He climbed the slope of his land grant—approximately 200 acres from the shoreline up and over the rise—and built his house on the hillside. Legend has it that a driving rainstorm washed that first house down the hill. So he set to building a small stone house, with walls two feet thick, a kitchen and a parlor below, and lofts for sleeping above. Iain named it Moidart, for the place he’d left behind. Here, in this new country, above the waves of St. Georges Bay, he and his wife raised 12 children.

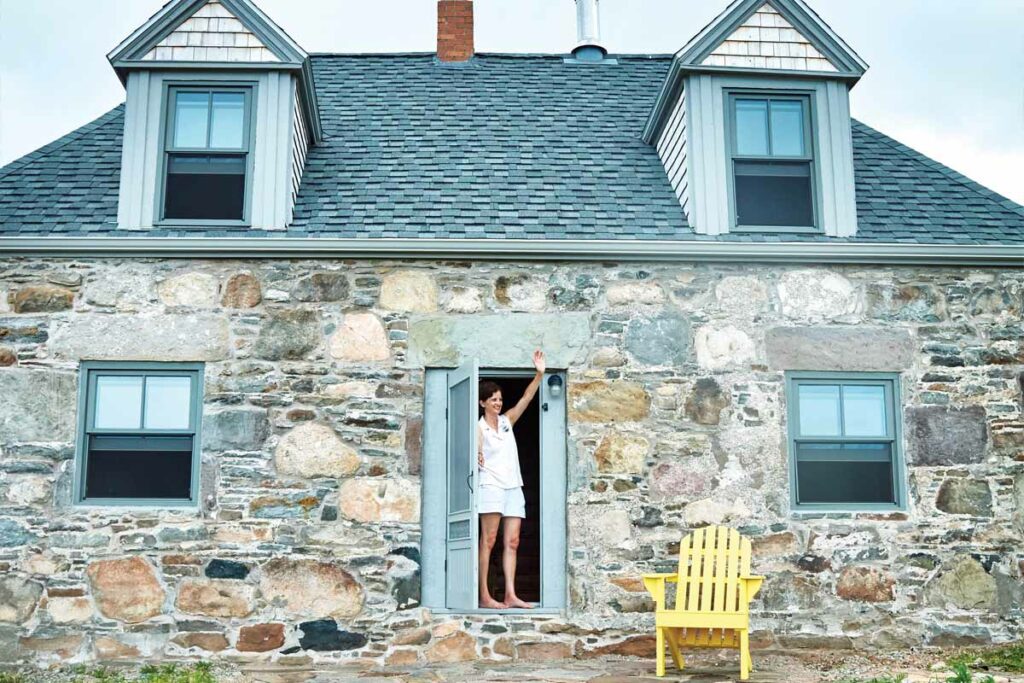

It’s been two centuries since Iain vowed that his house would withstand Creignish’s fierce winds, and it has. Perhaps more surprisingly, it has also found its way back into the hands of one of his direct descendants. After the property passed out of the family in the 1930s, Iain’s great-great-great-granddaughter, Lorrie MacKinnon, purchased the cottage in 2012. In the years since, she and some talented local craftspeople have worked to restore the stone building to something close to its original beauty. Lorrie and her craftspeople peeled back two centuries of “improvements” from her cottage’s structure. The stone walls of the kitchen and the wooden-beamed ceiling had been covered with drywall, the ceiling height reduced to under seven feet. The wooden floors of the kitchen had been hidden with then-fashionable linoleum sometime in the mid-20th century; the parlor floor and stairs “upgraded” with orange shag carpet, and in places underneath, the spruce wood had been painted brown, no doubt an ancestor’s proud effort at keeping the home fresh and tidy. An unused cellar crawl space under the kitchen had been packed with insulation, which was soggy and useless by the time Lorrie took possession.

It’s been two centuries since Iain vowed that his house would withstand Creignish’s fierce winds, and it has. Perhaps more surprisingly, it has also found its way back into the hands of one of his direct descendants. After the property passed out of the family in the 1930s, Iain’s great-great-great-granddaughter, Lorrie MacKinnon, purchased the cottage in 2012. In the years since, she and some talented local craftspeople have worked to restore the stone building to something close to its original beauty. Lorrie and her craftspeople peeled back two centuries of “improvements” from her cottage’s structure. The stone walls of the kitchen and the wooden-beamed ceiling had been covered with drywall, the ceiling height reduced to under seven feet. The wooden floors of the kitchen had been hidden with then-fashionable linoleum sometime in the mid-20th century; the parlor floor and stairs “upgraded” with orange shag carpet, and in places underneath, the spruce wood had been painted brown, no doubt an ancestor’s proud effort at keeping the home fresh and tidy. An unused cellar crawl space under the kitchen had been packed with insulation, which was soggy and useless by the time Lorrie took possession.

It took three months of deconstruction before Lorrie could decide where to start with restoration. She pitched in where she could, making 10 trips over 20 months from her home in Oakville, Ont. “I didn’t want to outsource everything and just arrive and look at things. I had to have some skin in the game,” she says. “I found a fishing gaff upstairs, put on a haz-mat suit, and pulled the insulation out of the cellar.” She hired Blaise Sampson, a contractor from nearby St. Peter’s, to remove the drywall, the carpet, and the linoleum, taking everything back to the stone walls and wooden beams. The parlor walls and the two-foot-deep window wells were faced with hemlock boards, probably original to the structure.

The considerations weren’t simply cosmetic, and the job might have daunted someone without a connection to the property. There was a crack in the back stone wall large enough to put your hand through, and that wall bulged out, its structure—and the building’s, as a result—compromised. The wiring needed to be replaced. The roof needed redoing. Almost all the windows needed replacing. A new septic system and well were required. The heat sources—an oil heater in the parlor and a wood-coal stove in the kitchen—had to go. How much did it cost? “Let’s just say it’ll be an extra 10 years before I retire,” says Lorrie with a laugh.

The considerations weren’t simply cosmetic, and the job might have daunted someone without a connection to the property. There was a crack in the back stone wall large enough to put your hand through, and that wall bulged out, its structure—and the building’s, as a result—compromised. The wiring needed to be replaced. The roof needed redoing. Almost all the windows needed replacing. A new septic system and well were required. The heat sources—an oil heater in the parlor and a wood-coal stove in the kitchen—had to go. How much did it cost? “Let’s just say it’ll be an extra 10 years before I retire,” says Lorrie with a laugh.

But there was beauty too. The wooden ceiling beams—likely cut from wood on the property—were rounded, a flourish not often seen in the area’s original humble homes, and bore the distinctive marks of an adze. The stone wall of the perimeter was actually two stone walls, one set inside the other with the gap between filled with rubble, in what Lorrie thinks was an early technique for boosting the warmth of the house. The wooden floor in the parlor was a later addition, purchased from a lumberyard, the yard’s stamp still visible on one of the planks. Upstairs, the roof beams were held in place by wooden pegs. The two dormer windows facing St. Georges Bay had been added almost 100 years after the cottage’s construction and were supported with tree branches, the bark still intact.

But there was beauty too. The wooden ceiling beams—likely cut from wood on the property—were rounded, a flourish not often seen in the area’s original humble homes, and bore the distinctive marks of an adze. The stone wall of the perimeter was actually two stone walls, one set inside the other with the gap between filled with rubble, in what Lorrie thinks was an early technique for boosting the warmth of the house. The wooden floor in the parlor was a later addition, purchased from a lumberyard, the yard’s stamp still visible on one of the planks. Upstairs, the roof beams were held in place by wooden pegs. The two dormer windows facing St. Georges Bay had been added almost 100 years after the cottage’s construction and were supported with tree branches, the bark still intact.

Lorrie’s goal was to honor the cottage’s past while creating a retreat comfortable enough for the present. On the main floor, that meant opening up a tiny bedroom that had been enclosed at the back of the house and sharing that floor space with the parlor. Upstairs, two small bedrooms on the north side became one, that large space mirrored on the other side of the center stairs, so that the second floor now consists of two large bedrooms, each with a dormer window facing the bay. Throughout, Lorrie left the ceilings exposed to the beams, so that the bedrooms now enjoy cathedral ceilings, while the main floor rooms feel airier.

And, of course, there was the structural work. Local stonemasons spent hours removing silicone and broken mortar, repairing cracks in the walls, and fixing the bulge in the back wall. One side and the front of the cottage had been whitewashed from the 1930s on, with the other walls left bare. The beautiful purple, brown, green, and grey of that bare stone—granite, sandstone, and whatever else its first builders found in the area—convinced Lorrie to have the other exterior walls cleaned back to their natural surfaces. The porch had been sided in aluminum and was structurally sound; inspired by a shingled lean-to in an early photo of the cottage, Lorrie decided to keep the porch but to replace the siding with wood shingles.

And, of course, there was the structural work. Local stonemasons spent hours removing silicone and broken mortar, repairing cracks in the walls, and fixing the bulge in the back wall. One side and the front of the cottage had been whitewashed from the 1930s on, with the other walls left bare. The beautiful purple, brown, green, and grey of that bare stone—granite, sandstone, and whatever else its first builders found in the area—convinced Lorrie to have the other exterior walls cleaned back to their natural surfaces. The porch had been sided in aluminum and was structurally sound; inspired by a shingled lean-to in an early photo of the cottage, Lorrie decided to keep the porch but to replace the siding with wood shingles.

Inside, the carpenter sanded and restored floors and stairs by hand, taking the wood back to its original finish. He recreated a trap door in the parlor to allow access to a second cellar found under the floor. (It was connected to the main cellar, under the kitchen, by a narrow tunnel that Lorrie discovered when she first cleared out the kitchen cellar. “I thought it must lead to another cellar, but was surprised by how much deeper, drier, and tidier the second cellar turned out to be,” she says.) In the bedrooms, Howe suggested enclosing the tops of the stone walls—where they meet a slanted roof, about two feet up from the floor—with hemlock boards rescued from the parlor so that each room’s exterior walls became edged in a wide ledge. The bonus? Wiring that would otherwise be a challenge to place along the stone walls could be hidden beneath the wood.

Inside, the carpenter sanded and restored floors and stairs by hand, taking the wood back to its original finish. He recreated a trap door in the parlor to allow access to a second cellar found under the floor. (It was connected to the main cellar, under the kitchen, by a narrow tunnel that Lorrie discovered when she first cleared out the kitchen cellar. “I thought it must lead to another cellar, but was surprised by how much deeper, drier, and tidier the second cellar turned out to be,” she says.) In the bedrooms, Howe suggested enclosing the tops of the stone walls—where they meet a slanted roof, about two feet up from the floor—with hemlock boards rescued from the parlor so that each room’s exterior walls became edged in a wide ledge. The bonus? Wiring that would otherwise be a challenge to place along the stone walls could be hidden beneath the wood.

The carpenter rescued a banister from an old home and reproduced a missing spindle. He turned his skill to other projects as well: crafting a door from the kitchen to the porch, building a base for a bookshelf, and restoring a wool winder and spinning wheel that Lorrie thinks might have traveled to the cottage from Scotland.

While Lorrie hoped their work would reveal a working fireplace in the parlor, in fact it revealed simply a hole from the wall into the chimney, probably for a wood stove pipe, with a wooden mantel above it. Rather than install a fireplace, she opted instead to face the wall with stone and put in a wood stove. On the kitchen side, she installed an ancient wood stove once owned by an old friend.

While Lorrie hoped their work would reveal a working fireplace in the parlor, in fact it revealed simply a hole from the wall into the chimney, probably for a wood stove pipe, with a wooden mantel above it. Rather than install a fireplace, she opted instead to face the wall with stone and put in a wood stove. On the kitchen side, she installed an ancient wood stove once owned by an old friend.

Two years after she’d taken possession, Lorrie finally had her first night in the cottage. Since then, she’s been able to return every three months or so—for extended weekends or stays of several weeks, in all seasons and weather. While her father passed away before she purchased the property, her mother joins her on some visits. Lorrie’s time there is spent visiting extended family and friends, hiking the local trails and walking the nearby beaches, visiting the farmers’ market and taking in local dances and festivals. A garden she’s added in the last year also occupies her summertime. She’s happy now to have both a home base in Cape Breton and, with the restoration done, the free time to practice the language that once filled the tiny rooms of her ancestral home.

You can read the original article at cottagelife.com