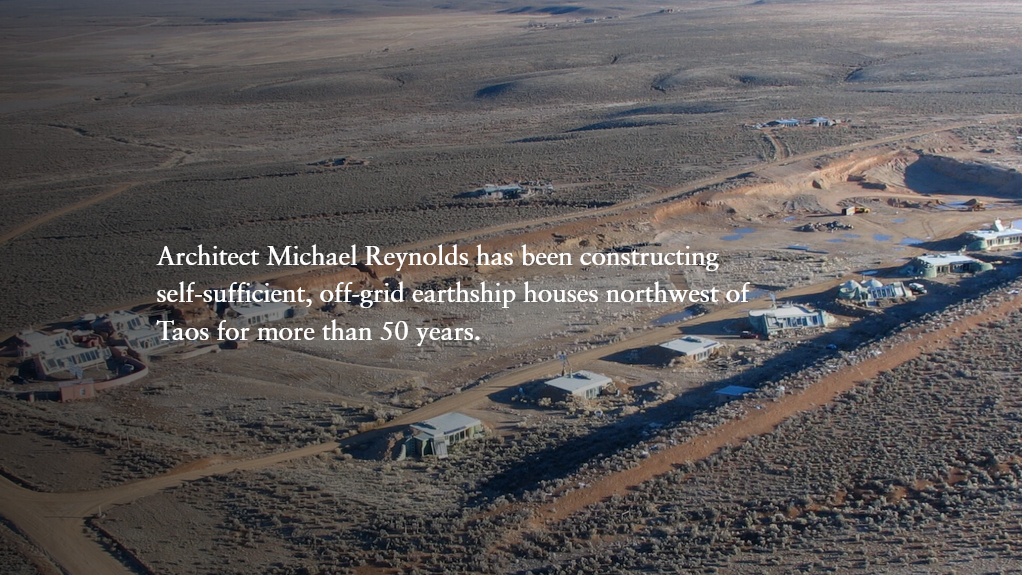

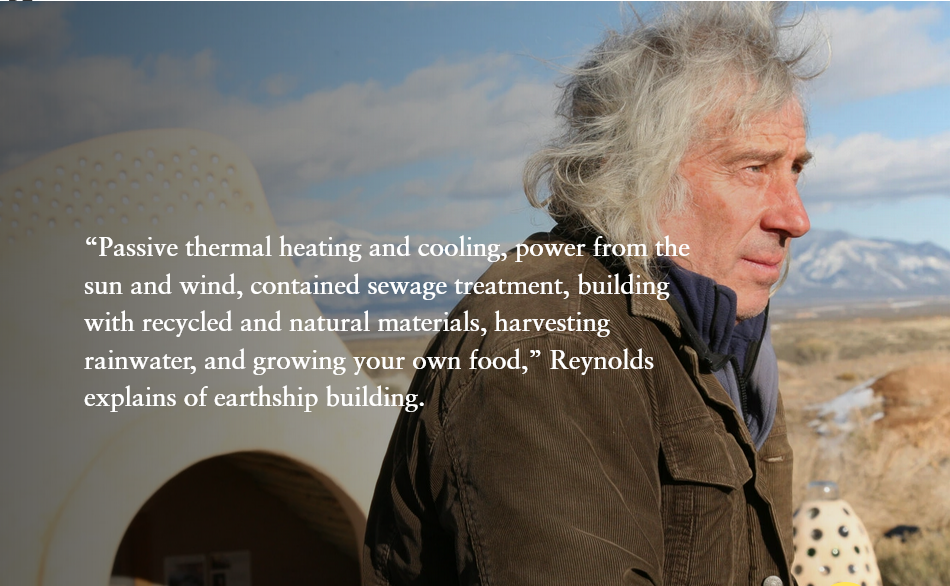

Michael Reynolds, the 77-year-old architect and founder of Biotecture Enterprise has been experimenting near Taos, New Mexico for more than 50 years with constructing Earthships, self-sufficient off-grid houses that harvest their own electricity, water and heat. “We build according to six principles,” Reynolds sums up his philosophy. “Passive thermal heating and cooling, power from the sun and wind, contained sewage treatment, building with recycled and natural materials, harvesting rainwater, and growing your own food.” These principles also explain why he calls them Earthships: Just like on a ship, the inhabitants have almost everything they need, independent of their surroundings.

Michael Reynolds, the 77-year-old architect and founder of Biotecture Enterprise has been experimenting near Taos, New Mexico for more than 50 years with constructing Earthships, self-sufficient off-grid houses that harvest their own electricity, water and heat. “We build according to six principles,” Reynolds sums up his philosophy. “Passive thermal heating and cooling, power from the sun and wind, contained sewage treatment, building with recycled and natural materials, harvesting rainwater, and growing your own food.” These principles also explain why he calls them Earthships: Just like on a ship, the inhabitants have almost everything they need, independent of their surroundings. When you enter the house through one of the artfully crafted massive wood doors, an earthy smell and tropical air linger — behind the windows grow banana and fig trees, tomatoes, kale, potatoes and roses. The greenhouse serves as a humid, warm buffer zone between the living area and the cold desert outside. State-of-the-art solar panels provide power and hot water. Rain is collected on the metal roof, and the water is reused four times — first for drinking and showers, then to water the greenhouse, then to flush the toilets, and lastly, the gray water nourishes the Russian olive tree and shrubs in the garden outside. Though rains in Taos usually stay far under two inches per month, the collected water suffices for a thrifty family of four. Utility cost: zero.

When you enter the house through one of the artfully crafted massive wood doors, an earthy smell and tropical air linger — behind the windows grow banana and fig trees, tomatoes, kale, potatoes and roses. The greenhouse serves as a humid, warm buffer zone between the living area and the cold desert outside. State-of-the-art solar panels provide power and hot water. Rain is collected on the metal roof, and the water is reused four times — first for drinking and showers, then to water the greenhouse, then to flush the toilets, and lastly, the gray water nourishes the Russian olive tree and shrubs in the garden outside. Though rains in Taos usually stay far under two inches per month, the collected water suffices for a thrifty family of four. Utility cost: zero. Long dismissed as hippie havens, Earthships have made a surprising comeback in recent years as a real solution for many construction problems. As gas prices rise, hurricanes leave entire states without power for weeks, and the climate crisis raises awareness of precious clean drinking water and other resources, Earthships are taking off. More than 200,000 visitors check out the prototypes in Taos every year. The pandemic and the climate crisis have spurred interest in sustainable, off-grid homes. Nearly 200 students learn about Reynolds’ principles every year at the Earthship Academy in a month-long course, and the Earthships that are rented out nightly to tourists are almost always fully booked. And in an economy where supply chain issues rendered conventional construction materials expensive and scarce, the raw material for Earthships can be found in abundance: trash.

Long dismissed as hippie havens, Earthships have made a surprising comeback in recent years as a real solution for many construction problems. As gas prices rise, hurricanes leave entire states without power for weeks, and the climate crisis raises awareness of precious clean drinking water and other resources, Earthships are taking off. More than 200,000 visitors check out the prototypes in Taos every year. The pandemic and the climate crisis have spurred interest in sustainable, off-grid homes. Nearly 200 students learn about Reynolds’ principles every year at the Earthship Academy in a month-long course, and the Earthships that are rented out nightly to tourists are almost always fully booked. And in an economy where supply chain issues rendered conventional construction materials expensive and scarce, the raw material for Earthships can be found in abundance: trash.

Rows of stacked old tires, filled with dirt, insulate the U-shaped shell to the north. Squashed beer cans protrude from half-finished adobe walls. Hundreds of blue, green, brown and clear glass bottles, float horizontally in the walls, artfully filter the light.

The material is dirt cheap, but the construction is labor intensive. For many hours, a young crew of 12 pounds dirt into the tires that are stacked to form a wall and then covered with stucco. More than a thousand tires are upcycled in the back wall of a two-bedroom house. Reynolds recycles up to 20 tons of trash in every Earthship.

The material is dirt cheap, but the construction is labor intensive. For many hours, a young crew of 12 pounds dirt into the tires that are stacked to form a wall and then covered with stucco. More than a thousand tires are upcycled in the back wall of a two-bedroom house. Reynolds recycles up to 20 tons of trash in every Earthship.

“The house takes care of me, and I take care of the house,” 34-year-old Texan solar engineer Gaelan Kefauver says while smoothing out an adobe wall in a half-finished Earthship. He quit his job after working for well-known solar companies such as Tesla. “These companies say they want the best for the planet, but at the end of the day, it’s all about the bottom line,” he says and shakes his head. For the last three and a half years, he’s been helping Reynolds build Earthships, and he also bought a cheap lot nearby to build his own. “This here is more genuine, more authentic,” he says. He likes that Earthship living is “very simple.” “I might have to wait for a sunny day before I turn on the washing machine,” one of the Earthship owners says, “but that I have to be mindful how I use resources is exactly what I like about it.”

Not all Earthships are that simple anymore, though. The price tags have gone up. Phoenix, the fanciest Earthship, is currently for sale for $1.5 million. It sports artfully rounded walls with handmade metal ornaments, a koi pond, and a fireplace with a built-in waterfall. A millionaire couple nearby built themselves a luxury ship with a solar-powered sauna, jacuzzi and dishwasher. To power such amenities, they invested in larger solar panels and water cisterns big enough to fulfill these needs and wants.

Both with his building company Biotecture and his nonprofit Biotecture Planet Earth, Reynolds has built Earthships in over 50 countries on five continents, as far away as Australia and Africa. After the tsunami in 2004, he and his team traveled to Asia to build emergency shelters on the Andaman Islands; similarly in Mexico after Hurricane Rita in 2006, in Nepal after the devastating earthquake in 2015, and repeatedly after disasters in Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Malawi and numerous other countries. “These countries are overflowing with construction materials — tires, glass bottles, cans — and people welcome us with open arms,” Reynolds says. “In Haiti, children collected tons of plastic and glass bottles that we used as insulation in the walls.”

Both with his building company Biotecture and his nonprofit Biotecture Planet Earth, Reynolds has built Earthships in over 50 countries on five continents, as far away as Australia and Africa. After the tsunami in 2004, he and his team traveled to Asia to build emergency shelters on the Andaman Islands; similarly in Mexico after Hurricane Rita in 2006, in Nepal after the devastating earthquake in 2015, and repeatedly after disasters in Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Malawi and numerous other countries. “These countries are overflowing with construction materials — tires, glass bottles, cans — and people welcome us with open arms,” Reynolds says. “In Haiti, children collected tons of plastic and glass bottles that we used as insulation in the walls.”

Even at home in the US, Reynolds and his 44 employees watched with concern as Americans were left without power and heat after the winter storm in Texas in 2021, and after hurricanes repeatedly destroyed the infrastructure in Puerto Rico. The five Earthships they built in Puerto Rico are still intact, Reynolds says, and reliably provide energy with their solar panels and clean drinking water with their rain catchers.

You can read the original article at reasonstobecheerful.world