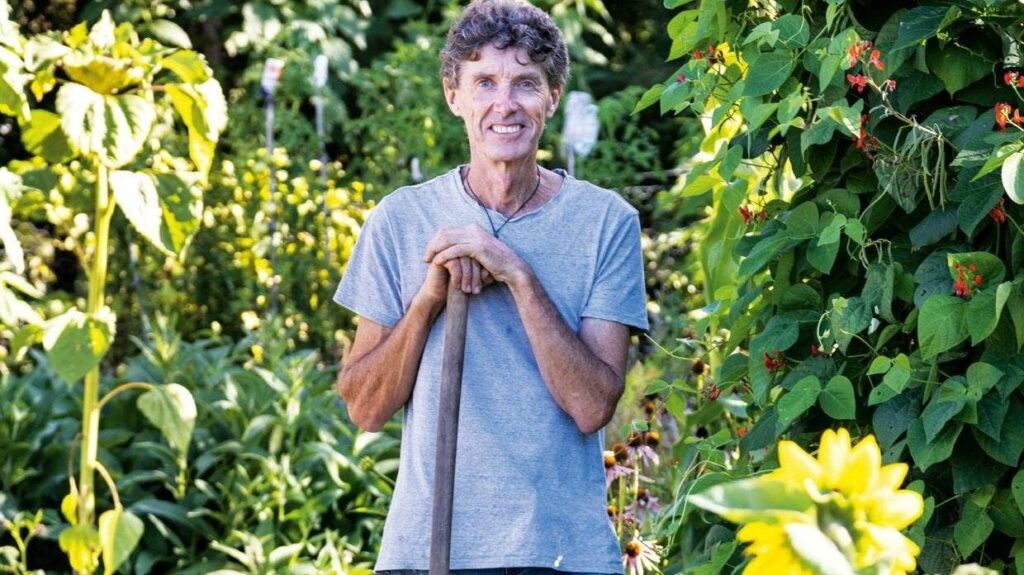

A lush edible oasis of forest garden is grown and lovingly tended by Garry and Ali Foster. Using no-dig, permaculture principles, Matahiwi Forest Garden celebrates balance, diversity and resilience. What was once a thin layer of riverbed silt is now a thriving ecosystem offering sustenance for several households.

The Fosters strive to live in partnership with nature: Ali writes conservation-themed children’s stories and Garry works full-time as a permaculturist. “The work of the gardener is to spend time in the garden, watching and listening,” he says.

The Fosters strive to live in partnership with nature: Ali writes conservation-themed children’s stories and Garry works full-time as a permaculturist. “The work of the gardener is to spend time in the garden, watching and listening,” he says.

As stewards of the land, Garry and Ali began by planting natives. The vision of a forest garden emerged over several decades. “We don’t have to sacrifice planting trees in order to grow food,” explains Garry. “The two are complementary – the forest supports edibles by creating microclimates. Essentially, the forest shelter creates the ideal conditions to sustain the lower layers of sub-canopy, shrubs, herbaceous plants and ground-covering edibles. Matahiwi Forest Garden has around 60 fruit trees and an abundance of different berries.”

The flow of the garden is designed around a series of clearings connected by curved paths. “As a species, we enjoy the feeling of following a curved path to emerge into a warm sunny clearing. Our natural habitat is at the forest edge, with shelter at our back and the sun on our face. We want our garden to be a joyous and relaxing experience, for ourselves and visitors,” explains Garry.

The flow of the garden is designed around a series of clearings connected by curved paths. “As a species, we enjoy the feeling of following a curved path to emerge into a warm sunny clearing. Our natural habitat is at the forest edge, with shelter at our back and the sun on our face. We want our garden to be a joyous and relaxing experience, for ourselves and visitors,” explains Garry.

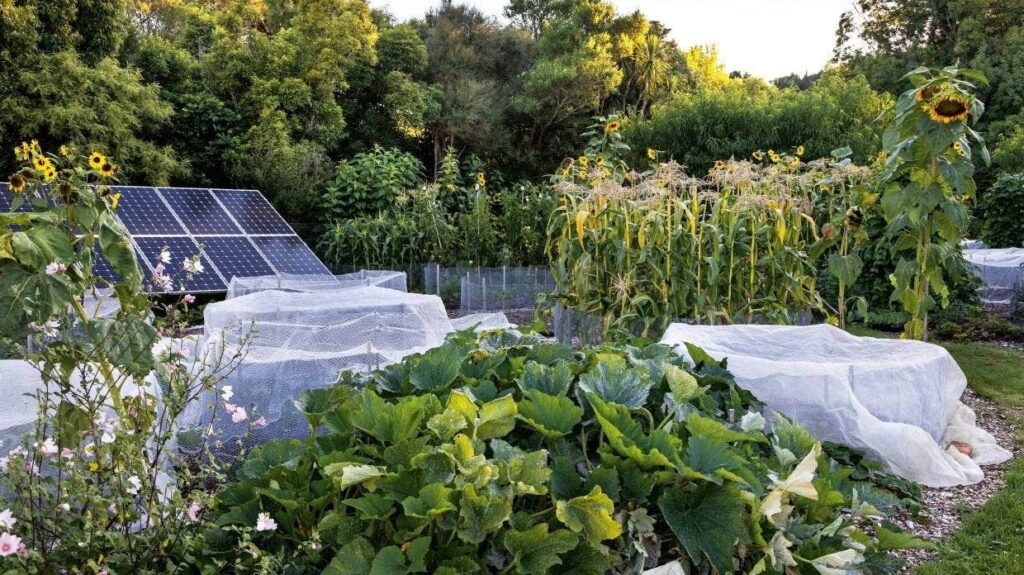

Garry and Ali’s goals are to feed the three households on their property from the garden year-round. While Garry says they haven’t achieved total self-reliance yet, they’re getting closer to it and gaining efficiencies all the time. As part of a holistic approach to building self-reliance, the Fosters also use solar energy, composting toilets and collect rainwater.

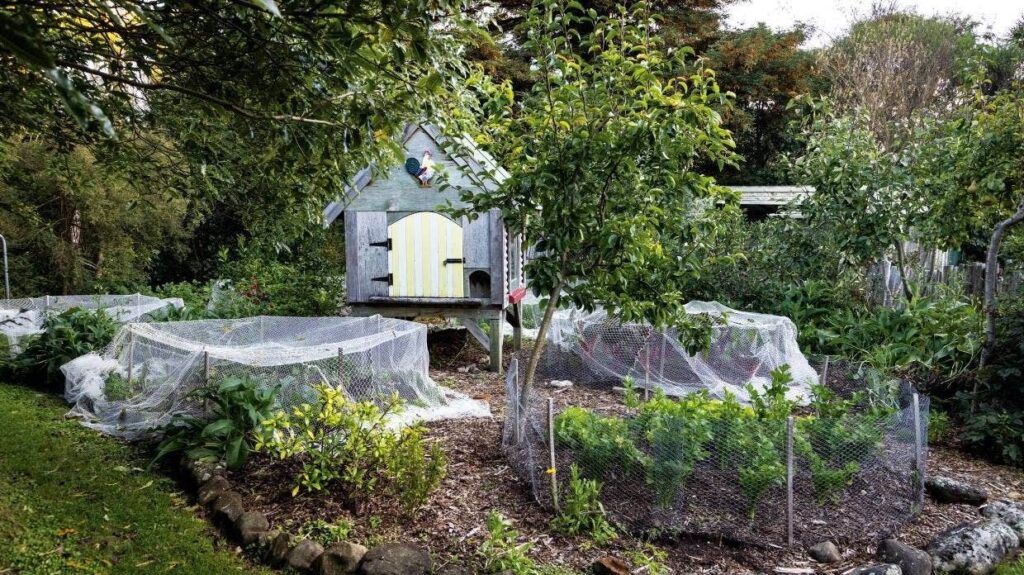

Twenty years ago, they made a firm decision not to spray. “That really committed us to finding natural solutions to managing pests and predators.” Sometimes it means delaying growing certain crops such as carrots (to avoid the slugs) and sometimes it means using a barrier such as insect mesh.

Twenty years ago, they made a firm decision not to spray. “That really committed us to finding natural solutions to managing pests and predators.” Sometimes it means delaying growing certain crops such as carrots (to avoid the slugs) and sometimes it means using a barrier such as insect mesh.

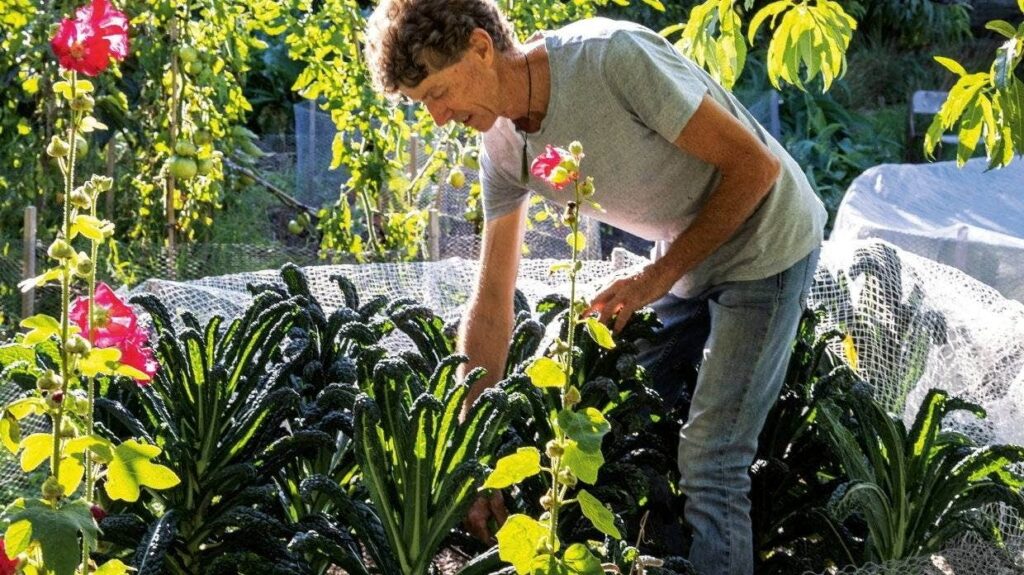

In the permaculture forest garden, there’s strength garnered from growing a diversity of crops – a way to insulate us from the challenges of growing food in a changing climate. “Monocrops put you in a very vulnerable situation,” says Garry. “Plants are like people, they don’t do well under constant stress. The best defense against pests and diseases is to grow rich healthy soil – that’s the engine room of the garden.”

Gary makes his own hot compost which calls for around 40% woodchips, 40% lawn clippings and 20% cold compost, including food scraps from each household, wood ash, and biochar. The process from start to finish depends on the fineness of the organic matter but as a guide, it’s ready to apply in three to four months.

Gary makes his own hot compost which calls for around 40% woodchips, 40% lawn clippings and 20% cold compost, including food scraps from each household, wood ash, and biochar. The process from start to finish depends on the fineness of the organic matter but as a guide, it’s ready to apply in three to four months.

Then it’s put to work in Garry’s crop circles. Fifty of these round beds, each with a diameter of 2.4m, are dotted throughout the forest garden and in permaculture zones one and two – close to the house for easy access. The circles are created with tall chicken wire – a handy base to throw over a cover of insect mesh.

The compost works as mulch and fertilizer. It also means Garry doesn’t have to think about rotating crops because the soil biology is constantly fed by the compost.

Every five years, he blankets the garden in a thick layer of woodchips. Not cultivating the soil allows it to retain structure, lock in moisture, inhibit weeds and store carbon. “The living soil houses millions of good bacteria and fungi. To disturb the balance would be akin to bulldozers tearing up our homes. Nature doesn’t till the earth so neither should we.”

Every five years, he blankets the garden in a thick layer of woodchips. Not cultivating the soil allows it to retain structure, lock in moisture, inhibit weeds and store carbon. “The living soil houses millions of good bacteria and fungi. To disturb the balance would be akin to bulldozers tearing up our homes. Nature doesn’t till the earth so neither should we.”

As he reaches for some autumn raspberries in the cool shade of the forest garden, Garry muses: “One day I’d like to think we’ll throw away the cutlery and just walk out into the garden to eat.”

You can read the original article at www.stuff.co.nz