Ross and Kristin Ulibarri live in a three-bedroom, two-bathroom home in Valverde Commons, a senior co-housing community within walking distance of historic Taos Plaza in New Mexico. Its sculpted adobe-style exterior makes it look like a traditional Southwestern dwelling.

The house has triple-glazed windows and air-tight insulation, so it rarely needs any heating beyond the solar gain from its south-facing windows. “The house is basically wrapped.” Kristin says. “It’s got this heavy plastic basin under the slab so there are no air leaks. Because of that, we have to have an energy recovery ventilator to not die of asphyxiation.” That ventilator helps keep the air temperature around 70 degrees all year. The little electricity this net-zero home uses is generated by solar panels.

The house has triple-glazed windows and air-tight insulation, so it rarely needs any heating beyond the solar gain from its south-facing windows. “The house is basically wrapped.” Kristin says. “It’s got this heavy plastic basin under the slab so there are no air leaks. Because of that, we have to have an energy recovery ventilator to not die of asphyxiation.” That ventilator helps keep the air temperature around 70 degrees all year. The little electricity this net-zero home uses is generated by solar panels.

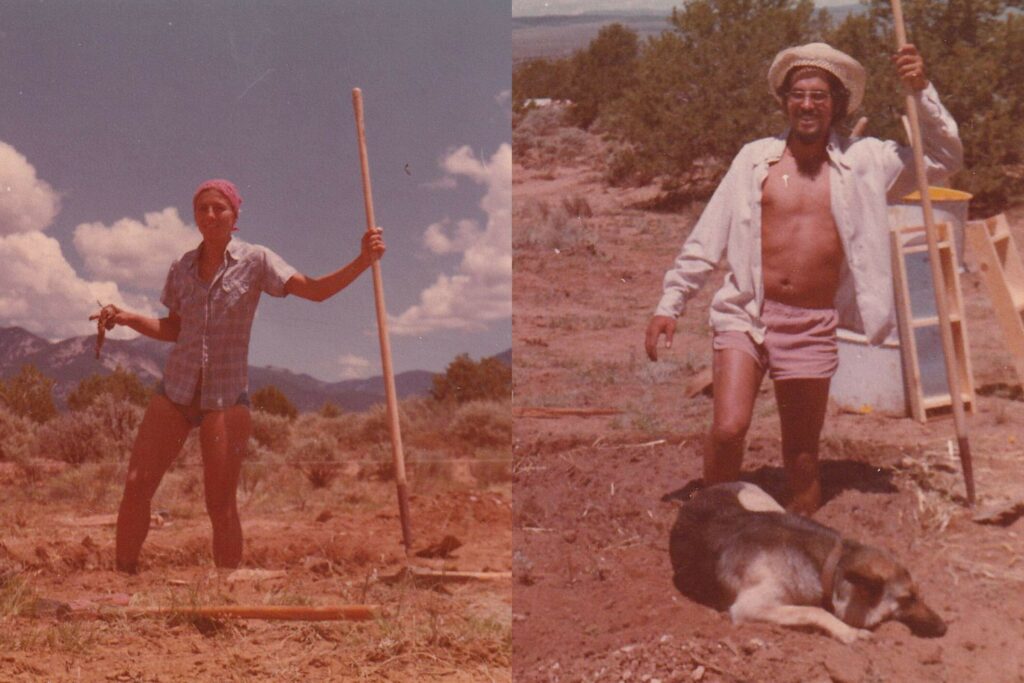

Before they came to this, they spent 40 years in another eco-friendly home on the other end of the technological spectrum: a small adobe dwelling they built themselves in the 1970s.“$10 a square foot is what it cost us,” says Ross, “and our entire youths.”

Before they came to this, they spent 40 years in another eco-friendly home on the other end of the technological spectrum: a small adobe dwelling they built themselves in the 1970s.“$10 a square foot is what it cost us,” says Ross, “and our entire youths.”

They read books on adobe construction, got permits for plumbing and electrical work, and covered their south-facing, earthen home in traditional mud-plaster. They gathered aspens for vigas and latillas — a traditional ceiling made of peeled logs and sticks — and built a life far from the mainstream.

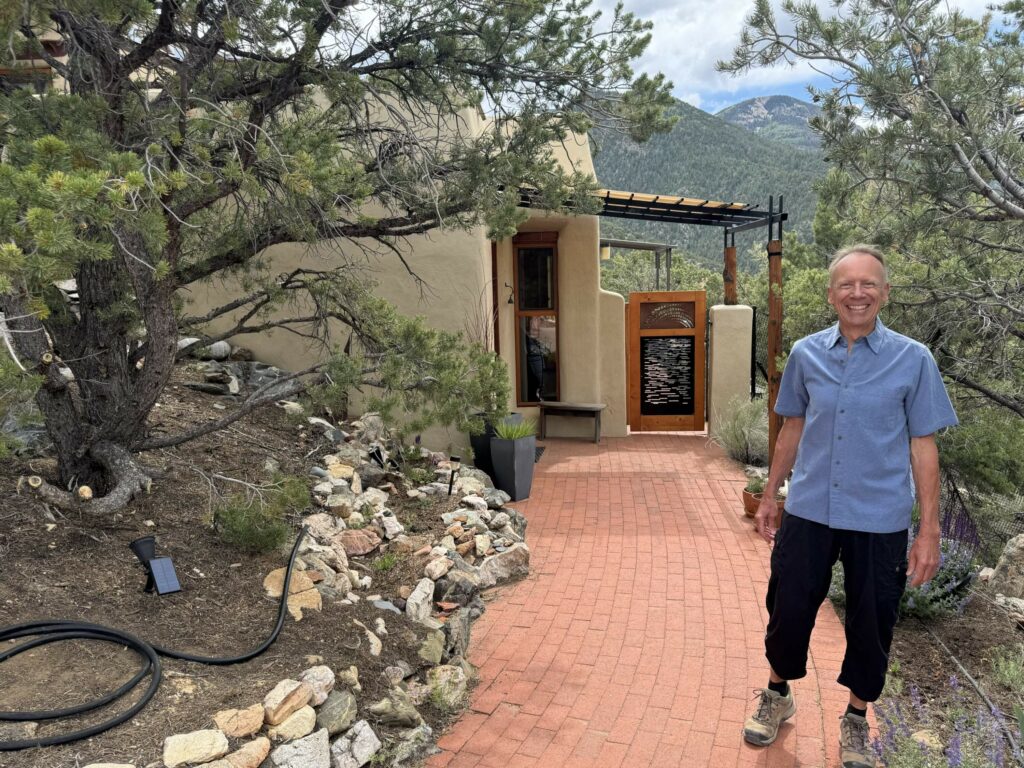

Karlis Viceps has been designing green homes in the area since the early 1980s, including his own, which is literally dug into a hillside overlooking Taos. Karlis and his wife built their home to be super efficient. The house stores the day’s solar heat with Trombe walls: thick, south-facing walls that are stuccoed black and tucked behind a few inches of glass and air. They trap and absorb heat when the sun is up and slowly release it through the night. If he needs additional heat, there’s a small wood stove fed by the pinyon-juniper in his backyard.

Karlis Viceps has been designing green homes in the area since the early 1980s, including his own, which is literally dug into a hillside overlooking Taos. Karlis and his wife built their home to be super efficient. The house stores the day’s solar heat with Trombe walls: thick, south-facing walls that are stuccoed black and tucked behind a few inches of glass and air. They trap and absorb heat when the sun is up and slowly release it through the night. If he needs additional heat, there’s a small wood stove fed by the pinyon-juniper in his backyard.

Karlis recycles rainwater. There’s even a composting toilet, opposite a window that looks out over the valley and mountain vistas. “I call it the best seat in the county,” he says. The house is exceedingly cozy and full of soothing textures, from exposed wood beams to straw-flecked adobe walls in the bedroom. “I think of the comfort,” Karlis says, “and the feeling that you can live in luxury with very little.”

Karlis recycles rainwater. There’s even a composting toilet, opposite a window that looks out over the valley and mountain vistas. “I call it the best seat in the county,” he says. The house is exceedingly cozy and full of soothing textures, from exposed wood beams to straw-flecked adobe walls in the bedroom. “I think of the comfort,” Karlis says, “and the feeling that you can live in luxury with very little.”

Anita Otilia Rodríguez built her house out of adobe in the 1970s, using techniques she learned from enjarradoras — craftswomen in the Hispanic villages and Indigenous Pueblos of New Mexico. Those homes are still standing and housing people after hundreds of years. “This is the heartland of the adobe-using cultures in North America. We have passed on by oral tradition the technologies to support that and it’s a system,” Rodríguez says. “It’s more than just building materials.”

Anita Otilia Rodríguez built her house out of adobe in the 1970s, using techniques she learned from enjarradoras — craftswomen in the Hispanic villages and Indigenous Pueblos of New Mexico. Those homes are still standing and housing people after hundreds of years. “This is the heartland of the adobe-using cultures in North America. We have passed on by oral tradition the technologies to support that and it’s a system,” Rodríguez says. “It’s more than just building materials.”

There’s a dome above her entrance, hand-sculpted archways, and a wood-fired oven made of adobe on the back patio, its chimney tapering off above the traditional ceiling made of peeled logs and sticks. Inside, the walls are plastered with a micaceous red clay found nearby that sparkles like hammered copper. In another home that might steal the show, but Rodríguez’s walls are also adorned with her own paintings: vivid scenes of brightly colored skeletons depicting life and death in the desert.

There’s a dome above her entrance, hand-sculpted archways, and a wood-fired oven made of adobe on the back patio, its chimney tapering off above the traditional ceiling made of peeled logs and sticks. Inside, the walls are plastered with a micaceous red clay found nearby that sparkles like hammered copper. In another home that might steal the show, but Rodríguez’s walls are also adorned with her own paintings: vivid scenes of brightly colored skeletons depicting life and death in the desert.

At 83 years old, Rodríguez has seen Native communities and traditional ways of building supplanted by a modern system that she says is isolating people and destroying the environment. “In 1847, the United States conquered half of Mexico, Taos included, and everything changed. We changed from a communal, collective form of building, then suddenly capitalism was introduced and the competitive construction industry,” she says, “and it is not working. We’ve got 14% of Americans who have no homes. Cement accounts for 8% of planetary pollution, all by itself.”

Rodríguez points to her own floor. “This has no cement under it. It’s 35 years old, it’s completely waterproof, and it has subfloor heating underneath it. And that is one of the techniques passed on by the enjarradoras,” she says. “So we have not only the material, we have the technology, and women and children and elders can use this building material. Our houses are almost like the shells of an oyster — they’re part of us. And they form our relationships with each other and with the environment. We’re just going to have to change.”

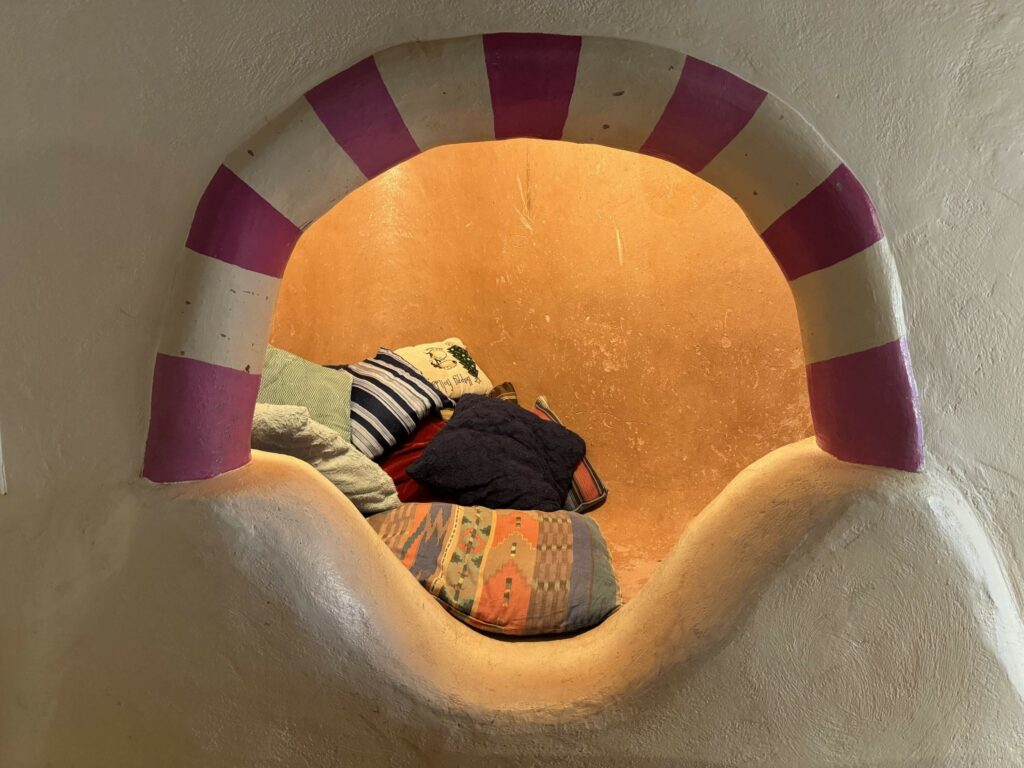

Dream Tree Project is a shelter and transitional home for young people in Taos with nowhere else to go. Architect Mark Goldman wanted the building to feel warm, welcoming and safe. Because the project was publicly funded, it also had to be affordable and sustainable. He says adobe was the natural choice. “A handcrafted space can often feel so much more comfortable than the most state-of-the-art, high-tech, machine-processed materials. I think we build square rooms and flat walls and paint them because it’s a very efficient way to build, but this is kind of sculptural,” Goldman says. “There’s a primal, cellular comfort. It’s almost like being in a cave.”

Dream Tree Project is a shelter and transitional home for young people in Taos with nowhere else to go. Architect Mark Goldman wanted the building to feel warm, welcoming and safe. Because the project was publicly funded, it also had to be affordable and sustainable. He says adobe was the natural choice. “A handcrafted space can often feel so much more comfortable than the most state-of-the-art, high-tech, machine-processed materials. I think we build square rooms and flat walls and paint them because it’s a very efficient way to build, but this is kind of sculptural,” Goldman says. “There’s a primal, cellular comfort. It’s almost like being in a cave.”

“We made all the adobe bricks here. We had over 100 volunteers who learned how to build with earth here. I say it’s using the best of the old and the best of the new,” Goldman says.

“We made all the adobe bricks here. We had over 100 volunteers who learned how to build with earth here. I say it’s using the best of the old and the best of the new,” Goldman says.

On a recent morning in June, Goldman mixes adobe in his backyard, scraping sand, straw and clay into a muddy mixture that will dry out in the sun. Half a century ago, the Ulibarris and Anita Rodríguez used the same process to build their homes. And it’s the same process that Indigenous people used 1,000 years ago to make houses out of this same patch of earth. It’s a reminder that while some of our technology might be new, what we now call sustainable design is at least as old as the ancient Pueblo in Taos.

You can read the original article at www.wbur.org

I bet the $10 per square foot figure excludes things like plumbing and electricity.