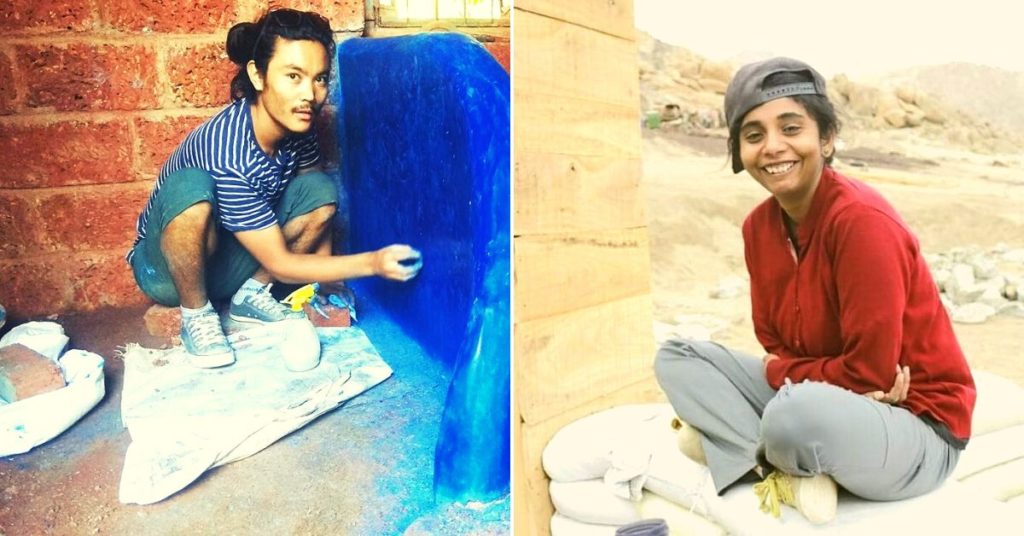

Stanzin Phuntsog (24) and Samyuktha S (29) are from the opposite ends of India, but they share a vision for sustainable architecture that is natural, eco-friendly, community-driven and hands-on. Three years ago they established Earth Building in order to promote these things. They have explored many earthen techniques like cob, earthbag, adobe, rammed earth and stone masonry. They are reclaiming indigenous knowledge and putting their own spin on it. They constructed an Earthbag Dome in Ladakh and an Adobe Farmhouse in Tamil Nadu.

Stanzin discovered his love for architecture, community building and natural materials at SECMOL, an alternative education center. After that he attended a two-year course at Swaraj University where he received more hands-on training in architecture based on the principle of self-designed learning. “I learned about sustainable architecture and its concepts through workshops, traveling around India and working on different projects,” he says.

This is where he met Samyuktha, who already had a formal degree in architecture and had worked for a year. “When I started studying architecture, I wanted to do something that was environment-friendly. During internships and even after college, I was doing projects with my professor to learn using natural techniques like lime plastering. But I wanted to learn more. One day, my professor told me about Swaraj University in Udaipur. After working for a year, I enrolled there,” she says.

“I had very minimal experience working hands on. At Swaraj, I was amazed to find out the kind of instinctual understanding Stanzin had about how to handle mud and natural materials. In many ways, he was a mentor who helped me transition from designing structures to actually putting my hand in the mud and making them. My understanding of natural materials and concepts of natural buildings was augmented by working with him. I doubt I would have progressed the way I did if it weren’t for Stanzin,” she recalls.

Their first major project was Samyuktha’s family home in Valukkuparai, a village where they built a five-room earthbag dome house. The entire structure is 1,200 square feet. This is where Earth Building did a lot of their initial experiments in natural building, laying the foundation of their future projects. “It’s an earthbag house shaped like a flower with a central circle and two petals on either side.” he says.

Due to the tropical climate, the dome was protected with a roof over it, using tiles that are placed on top of earthbags and protect the dome and all the other rooms from the rain.

“For the foundation, we dug the ground six feet until we arrived at a hard surface, following which we employed trained labor to do stone masonry work. When you dig through layers of mud in different areas, you reach a hard stone layer, and we generally stop there to establish a foundation. Once again, how deep you have to dig depends on the topography. Sometimes it’s just two feet, while other times we go up to six feet. This is how we have built foundations on all our projects till now. The walls were made of earthbags, for which we conducted workshops for volunteers from places as far as Rajasthan, Mexico and France. With a total of five rooms, this project used over 3,500 cement bags. Even my parents got involved with the project. My mom came down to cook for all of us, which further added to the communal spirit,” she recalls.

Earth Building does not have a base headquarters or main office anywhere; they go wherever the projects are happening. “When we started, we wanted to establish a community building exercise. This wouldn’t happen if we are not on site. A lot of our projects are workshop oriented and volunteer based. We want to stay on site, and it doesn’t matter where the place is situated. Both of us also like to travel a lot. It’s a great experience to understand the place, its inhabitants and their traditional forms of architecture. While making structures for our clients, we conduct workshops as well. Both of us learnt through workshops and working on different projects, especially for Stanzin, and that’s why we have taken this approach,” says Samyuktha.

“Working with skilled labor and student volunteers are completely different experiences. With volunteers, including interns studying at architecture schools or anyone with a genuine interest in natural buildings, it’s like a community of people coming together and wanting to seriously learn something. This is a learning environment where cooperation is key. Since we have volunteers who want to learn, they keep questioning us and it offers a lot of scope for us to refresh our knowledge base as well,” notes Stanzin.

“We had this project in Alibaug where the clients didn’t want a workshop and wanted us to solely focus on completing the finishes properly. Nonetheless, most of our clients want us to post workshops. For example, when we worked with the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives (HIAL) in Leh to make an Earthbag Dome, they wanted us to make it a learning project for their students. It also depends on the scale of the project. If it’s a bigger project, working with volunteers isn’t optimal,” she adds.

“Wherever we go, our first challenge is to figure the kind of soil locally available. While the formula for cement is universal, in natural buildings, you have to figure out what kind of soil these places possess.” Besides soil, Earth Buildings also look at the kind of skills found locally.

Another common thread in the projects is the use of either mud or lime plaster. “In hotter parts of South India, for example, there is a lot of rain and termite activity. Using earthen plaster in the interiors of my home hasn’t been a very good experience, and we have to constantly oil our wood. This is a major inconvenience. So, for this kind of climate, we use a lime plaster—there is a variant called lime surkhi, which allows for fine finishes since both lime and surkhi (red brick powder) bond better, possess greater water holding capacity and it’s not very time consuming,” says Samyuktha.

She adds that they sometimes also use the more expensive Tadelakht lime plaster—a water-proof Moroccan technique combining lime and olive oil soap and burnishing with stone. It is water resistant and that’s why they use it particularly in bathrooms.

For the Adobe Farmhouse in Pollachi, the duo laid down Kadappa stone on top of the walls to bring it together and also act as a barrier between mud and wood for termite protection. The roof is a hipped roof made of palm wood rafters with reused Mangalore tiles. For the internal and external plastering, they used a lime plaster and Tadelakht plastering for the bathroom, and lime surkhi plaster for the external walls.

The total built up area of this farmhouse is 840 sq ft with the foundation done with random rubble masonry and the plinth is dry stone masonry made with the assistance of local artisans. The walls were a mix of cob, adobe and stone masonry, while windows and doors were reclaimed from old houses and re-used.

“After the lockdown, we want to do projects and explore different parts of the country. It’s making an impact, but not enough. It would be useful if we could share our knowledge with others and vice versa so that more people start practicing sustainable architecture. We want to establish and set up a place where we can experiment and exchange ideas on using natural building materials. If more architects take interest in our kind work, the greater our impact will be,” concludes Samyuktha.

You can read the original article at www.thebetterindia.com

All images courtesy of Earth Building.

I am an architect. I want to contact them and need their contact details.

See https://www.facebook.com/mudhouses/